A crumbling parking lot sprawls over the lots around 215 2nd Street. Situated across from the entrance to St. Anthony Main, and just a stone’s throw from the monolithic grain elevators left over from the milling industry that was, this lot was a part of the deal in the sale of the General Mills property one lot over. Doran, a construction company, made a proposal to develop the parking lot into a block of housing units. They pitched their plan to the Minneapolis Heritage Preservation Commission on Oct. 10, and were met with opposition from both the commission and residents of the Marcy Holmes neighborhood.

The proposal was for a 26-story tower to stand in the corner of the lot, flanked by low-rise apartments and town homes with space for some retail, and a small park. The commission liked the proposed apartments and town homes, but could not get past the sheer height of the tower, the architectural centerpiece for the whole development. Previous designs had the tower taking up more of the block, but neighborhood feedback got Doran to slim the building’s profile down significantly. To make up for that, they made it taller to keep more interior space.

Guidelines for building in a historic district set rules for metrics like number of building materials used, height and density of a newly-built project. These guides are set to ensure that new developments match the look and character of existing structures. From their original plan, Doran had to scale back the primary colors of their building and the size, both of which were reflected in their new proposal after taking community feedback to heart. However, guidelines in the Mill District along the river dictate a maximum height of eight stories, a size they exceeded by more than double.

There are some cases in which variances can be applied for, which was what Doran asked for at their hearing on Oct. 10. They cited other tall buildings in the area as precedent, and argued that the need for high density housing in Minneapolis called for more large-volume units close to downtown.

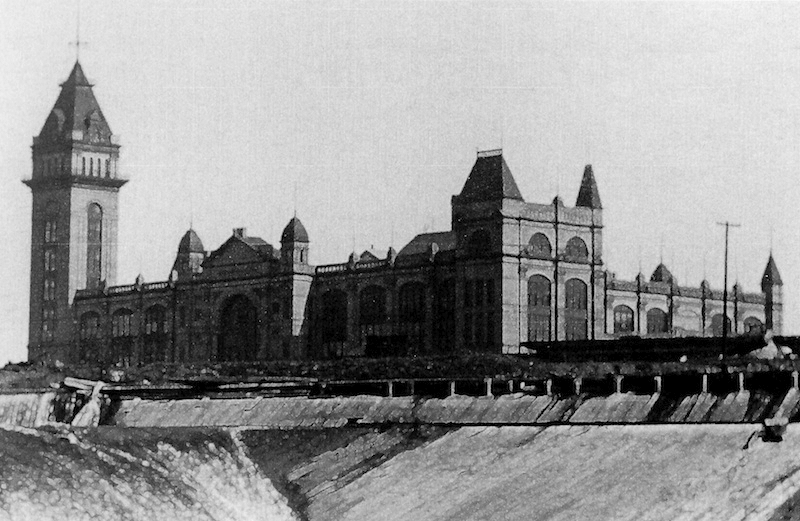

The lot itself bears little actual historical value as it is and always has been a parking lot, so Doran aspired to create historical value themselves. Their design for the building was based loosely on the Industrial Exposition Hall, a building demolished in 1940 that once stood just down the road where 2nd Street meets Central Avenue. The Exposition Hall was distinctive for its tall tower, and was the tallest building in Minneapolis for a time.

According to John Ferrier and Kelly Doran, the two applicants who spoke in front of the Preservation Commission, the feedback they have received from the community about the changes they made to their original designs has been mostly positive.

A speaker on behalf of the Marcy Holmes Neighborhood Association did agree that they approved of the changes made after their feedback was given; however, they had more suggestions for how the tower and town homes could better fit the needs of the community. The principal issue was still the height; one proposed fix was to have two shorter towers instead of one massive one, a change that could potentially reflect the design of the old Exposition Hall even further.

Abby Alldaffer, another potential neighbor for the building, spoke to the Preservation Commission as well. She claimed that units in this building would run starting at $1,200 a month, a very out-of-character price line for a neighborhood primarily made up of students and retirees.

“In an area where the average income is less than $20,000 a year, how is this appropriate?” she asked, going on to question why the city was encouraging high-density housing if rents were going to be high.

Rent costs in Marcy Holmes have inflated greatly, and Alldaffer worried that buildings in the same vein as the Doran project were contributing to that. Applicant Kelly Doran explained that he had applied to the city for affordable housing support, but funding had run out and his project was turned down, so they had to proceed with asking market-rates for units. The Minneapolis office for Community Planning and Economic Development confirmed that yes, occasionally funding to subsidize affordable housing does run out, but media contact Casper Hill did not return phone calls seeking further details.

Eric Wunderlich, speaking on behalf of Neighbors for East Bank Livability, questioned the support of hyper density, saying that the idea of more units equaling more affordability has yet to actually affect housing in the area, and instead just drives up property taxes for already-existing housing.

“What I don’t understand is why the city continues to believe in the myth of trickle-down housing,” said Wunderlich.

In the end, the Preservation Commission voted against approval of Doran’s variances, sending the developer back to the drawing board with a heap of community suggestions and a reminder that guidelines exist for a reason.

“We’re in a difficult position,” said Commissioner Susan Hunter Weir. “There has to be something really compelling about a development [in order to approve a variance to this degree], and it really doesn’t satisfy the city’s needs. There has to be something special going on, and I’m just not getting that.”

To the commissioners, the tower was just that: a tall tower that didn’t stand in keeping with the character of the community. They cited a passage in the guidelines for the district stating that the grain elevators on Second Street should maintain prominence in the profile of the neighborhood, and should not be obscured by taller buildings in the vicinity. The elevators measure up around eight stories, so Doran should observe those guidelines especially given the site’s proximity to them.

“I don’t really see why we have to have a tower of this type,” said Commissioner Dan Olson. “And I don’t really buy that the Exposition Hall sets the precedent. It’s not the Exposition Hall and it never will be.”

Below: Doran’s proposal for the 2nd Street site included a 26-story tower inspired by the Minneapolis Exposition Hall, which used to stand a few blocks away until it was demolished in 1940 (the tower stood for six more years after the Hall went down, but didn’t last). The Heritage Preservation Committee ruled that the tower was too tall, even after adjustments were made from the original design. (Graphic produced by Doran Construction. Photo courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society)