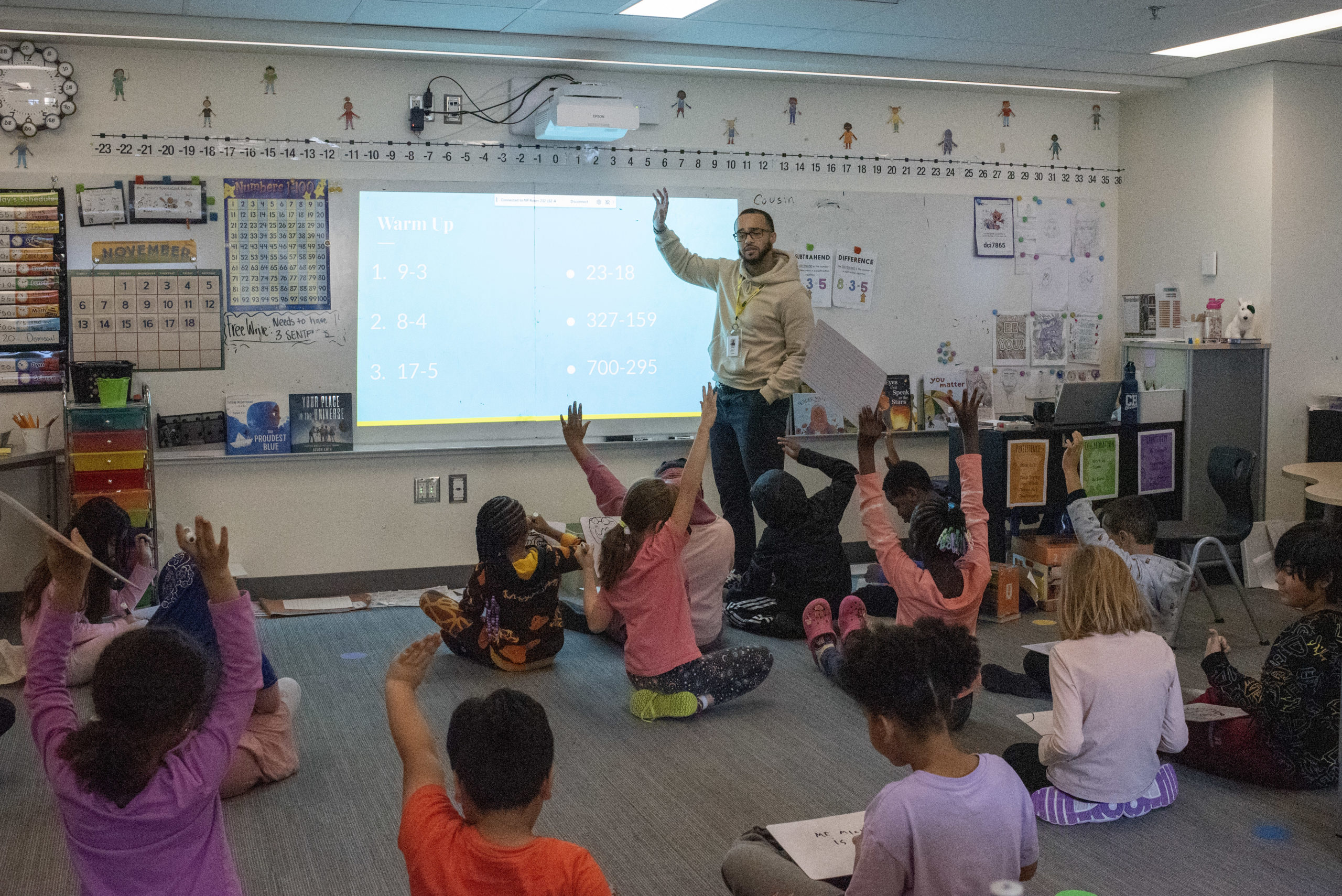

In a North Park School for Innovation third-grade classroom on the Monday before Thanksgiving, Devon Minke shepherded his class through several transitions. Students sat on the floor quietly as he explained how Wednesday’s flex learning day would work, then on to math. He announced a subtraction test for Tuesday and responded to their groans with reassurance. “I have seen all of you do your subtraction for the last two weeks and I promise you, all of you have gotten better.” Next, he orchestrated an orderly fetching of whiteboards and markers as he called out their names one by one. Two minutes of doodle time to get it out of their systems before they get to work, he told them, and he set a timer displayed on the screen in front of the room.

Down the hall from Minke is a second-grade classroom where Keon Lewis was also working on subtraction with his students. The activities were different – the class moved from group work where they’d been discussing math problems to a two-minute timed test – but the transitions were as carefully planned as Minke’s. Both men were calm, clear and positive, their students attentive. Their classroom management skills appeared to be those of seasoned teachers, which is notable, as this is their first year of teaching. Also notable is the fact that they are Black – because it is rare to find a Black man in an elementary school classroom.

“You can easily put all the Black male teachers in the state of Minnesota in one room,” said Markus Flynn, executive director of Black Men Teach, an organization that has supported Lewis and Minke since their senior year at Minnesota State University, Mankato (MSU). Flynn estimated that there are about 220 Black male teachers across the state, and Lewis and Minke’s experiences as K-12 learners bear that out. Minke only had one Black teacher, a 7th grade gym teacher; Lewis had none. (This year, only 18 out of 240 licensed teachers in the Heights school system are teachers of color or American Indian, according to communications director Kristen Stuenkel.)

Flynn suggested several reasons for this, which include the fact that 70% of Black students are in high-poverty schools that do not have adequate resources for student success. Another factor, he said, is “school-induced trauma.” Nationally, Black students across K-12 are three times as likely to be suspended or expelled as white students, and in Minnesota it’s eight times, he said. Black students make up 10% of the student population in Minnesota but are the subjects of 42% of all the discipline incidents. “So school can be a very trauma-inducing place. And then the next piece is obvious – lack of representation. They’re not seeing themselves,” Flynn said.

Only three out of the 20 students in Minke’s classroom identify as white, with similar demographics in Lewis’s class. “A quote that really resonates with me … is ‘You cannot be what you cannot see.’ I think for my students to be able to see me up here teaching — the positives and negatives that come with being a classroom teacher — I think they’re able to see that they can achieve these things, and they can be a teacher,” Minke said.

Data supports the importance of same-race teachers in academic success. Black students in elementary grades who did or didn’t have a Black male teacher showed dramatically different outcomes, said Jeff Cacek, North Park’s principal. He shared statistics cited on the Black Men Teach website, which come from two research reports published by the National Bureau of Economic Research. Those with a Black male teacher were 29% less likely to drop out of school. This number is 39% for very low-income Black students. And when classes of predominantly Black and brown students have a teacher of the same race, or ethnicity, they’re held to higher expectations 66% of the time, compared to only 35% of the time when they had a teacher who did not share their race or ethnicity,” Cacek said.

Those kinds of numbers are behind the mission of Black Men Teach, which encourages young Black men to consider a teaching career and provides what Flynn calls a “robust pathway of support” to those who choose teaching. That pathway includes scholarships, student teaching stipends, retreats, workshops, mentorships and emergency funds.

The organization recruits in high schools, providing fellowships and internships for students that give them the opportunity to visualize teaching as a career and teach social and emotional awareness to youngsters.

Black Men Teach works with teacher training programs at the university level as well. Flynn connected with Lewis and Minke during their senior year at MSU, where they were the only two Black students in the elementary teacher education program and only two of four men. “We were in spaces of predominantly white women,” said Lewis, a new experience for him; he grew up in the racially and culturally diverse Columbia Heights school system.

Both men talked about “difficult conversations” they needed to have with classmates and professors about racially ignorant or insulting comments and actions, such as the half-hour discussion they initiated during an arts education class when a spiritual – music borne of slavery – was presented in an insensitive and inappropriate way.

Lewis said that they went to the dean on several occasions to explain the ways in which their program was “not a safe space,” with the hope of improving it for future Black men. “It felt like it was an added pressure to discuss and educate and bring the Black perspectives into things,” said Lewis.

Minke said that during his student teaching in a Mankato school, he had to address situations in which staff members either said things or acted in certain ways toward certain groups of students. He wasn’t sure how to handle them, and Flynn provided the guidance and support he needed. “Black Men Teach was a staple in terms of creating a space and creating resources that have helped me push through … those kind of comfortability factors that come with stepping into the world of education.”

How did Minke and Lewis find their way to teaching? Minke is the eldest of nine children from St. Paul’s East Side, and some aspects of his story point to other barriers in Black men becoming teachers. There was a gap of about 50 years since the last person in his family had gone to college, and he didn’t understand much about financing his education, he said. He was surprised to learn that he needed to pay the tuition bill on the front end of the semester. Fortunately, Kenneth Reid, MSU’s director of African American Affairs, helped him navigate financial hurdles and obtain scholarships that helped him focus on his education. Black Men Teach also provided financial assistance, he said.

At first Minke wanted to be a pediatrician, with the aim of being of service to low-income communities and “people that look like me,” but a conversation during a dinner with Black university faculty at the beginning of his freshman year made him realize that he could achieve his goals “and more,” in a shorter amount of time by going into education.

Lewis started college with teaching in mind. He had worked with kids since he was 15 years old, in jobs with the Columbia Heights Department of Recreation. In high school he had the opportunity to volunteer as a teacher’s aide at Highland Elementary School. The students of color gravitated toward him, he said, and that’s when he realized the importance of having Black men in the classroom. “As diverse as Columbia Heights is, the teachers just didn’t reflect that,” he said.

As he started looking past graduation, Lewis encouraged Markus Flynn to consider Columbia Heights as a Black Men Teach partner district, and Flynn and Superintendent Zena Stenvik set it in motion. North Park had two teacher openings, principal Cacek said, and Minke and Lewis were hired. Ted Ngeh, another Black man who has taught at the school for eight years, was supported by Black Men Teach to be their mentor. For their classroom teachers, Black Men Teach provides instructional support, professional development and some student debt alleviation, Flynn said.

Their year is going well so far; both talked about learning to balance taking care of themselves with the time-intensive planning and preparation the job requires. Cacek said that he quickly learned that both are already very capable teachers who need relatively little support in classroom basics, but that Minke and Lewis are very eager to be coached. “They are like sponges, they just want to know, they want to learn, they want to be the best at what they do. They’re two very special young men.”

The students in their classes appear to be enjoying themselves, which is one measure of engagement, said Bondo Nyembwe, the district’s executive director of educational services and liaison with the Black Men Teach program. “The level of joy is high. … The engagement is powerful. There is a connection that we see,” he said.

That connection is also apparent in the story Cacek recounted about the Black second grader who walked into Lewis’ room during open house night, saw Lewis for the first time, and exclaimed “Yes!” accompanied by a fist pump.

It’s that kind of identification that Minke relishes. He said one of his Black students came up to him and told him that he hopes to become a teacher when he grows up. “For them to just be able to see me just even walking up here and … being a leader of the classroom, I think that shows them and inspires them that even if they don’t want to be a teacher, they can be a leader. They can be somebody that people look up to,” Minke said.

Below: Keon Lewis leads his second-grade class at North Park School for Innovation in Columbia Heights; Devon Minke’s third-grade class works on subtraction. Both men are first-year teachers supported by the organization Black Men Teach. (Photos by Karen Kraco)