A vacant lot near 18th Avenue and Marshall Street NE on the river side holds a bit of forgotten Minneapolis history. Now owned by the Minneapolis Parks and Recreation Board, it’s a tangle of wild grapevines and old cottonwood trees, strewn with old cobblestones, chunks of concrete and limestone. Recent human use is evidenced by a pile of vaping cartridges, broken liquor bottles and plastic water bottles. Near the center of the lot are what look like pieces of an old chimney made of yellow brick. It’s hard to believe a home once stood here, accompanied by a thriving ferry business.

The owner of the ferry was Captain John Tapper, who came to America from Dorset, England, in 1844. After fighting in the Mexican War, he worked as a teamster at Fort Snelling and later helped John Stevens build the first house in Minneapolis where the Federal Reserve Bank stands today. (The Stevens House was moved to Minnehaha Park in 1896.)

There were no bridges across the Mississippi River then. Boats were used to get goods and supplies to and from Nicollet Island or to the other side of the river, where the town of St. Anthony was just getting started.

A Sept. 3, 1939 Minneapolis Star-Journal article said early newcomers to the area sometimes employed a Dakota woman to paddle them across the river. “Although she was a good hand with the paddle, the current sometimes was so strong it upset her craft. Teams had to wait for low water to ford the river at Boom Island.”

Crossing the river

In 1847, Franklin Steele, who had claimed a large swath of land from Fort Snelling to St. Anthony Falls, saw an opportunity and strung a ferry line from Nicollet Island to the Federal Reserve site. No photos exist of the ferry, but it was described as a flat-bottomed boat attached to rope lines. The cable kept the boat from floating downstream and was used to haul it across the river. Edgar Folsum ran the ferry for one season.

Folsum did not seem cut out for the job. He once lost patience with a crew member who did not obey orders to cast off. In anger, he cast the rope which was “straining like a bow cord” himself, only to have it whip back at him and fling him 20 feet onto a sheet of ice.

His short tenure at the job may also have been due to an incident that made him the butt of several jokes. According to an account in History of Hennepin County and the City of Minneapolis, one of Reuben Bean’s daughters was out on the river in a canoe when it hit the ferry rope and capsized. Folsum rescued her and demanded her hand in marriage as payment. “But she, thinking the demand too high, exclaimed, ‘Put me back on the ferry rope.’” He left town soon after.

Tapper became the ferryman, making regular trips between the island and the west bank. People on foot paid 5 cents to use the ferry; if you drove a team of horses, you paid a quarter. If water sloshed overboard, you were handed a bucket to bail the boat.

Once, the boat collapsed, and a team of horses ended up in the river. They were saved, but the boat went over the falls and there was little left but kindling. Tapper, known for hanging on to his money, didn’t offer a discount.

First-year profits for the ferry were estimated at $300.

Dangerous work

Tapper also had his troubles on the river.

Stevens wanted to farm the land near his house, and he bought a small herd of cattle in Muscatine, Ia. To get them to his property, he had to ferry them across the river. According to History of Minneapolis and Hennepin County, Minnesota, “The only means of communication with St. Anthony was in a small skiff propelled by two pairs of oars, and the water route was above the Falls, and above Nicollet Island, where the current was so strong that it was fortunate when a landing was made any considerable distance above the terrible rapids.” It took Tapper and another “brawny boatman” to get the boat and its cargo across the river.

In another incident, Tapper and Simon Stevens rescued a seven-year-old boy who was alone in a boat heading rapidly toward the falls. His older brother had stepped out of the boat, but hadn’t secured it. The men had to row “so near the brink of the falls themselves, that for a moment, it was doubtful which would be victorious, the strong current or their strong arms. Their best efforts at first failed to show any gain, but at last inch by inch, they pulled away from their perilous situation.” The boy, J.J. Pottle, grew up to be a carriage manufacturer in the city.

One of Tapper’s boats was stolen by a steady customer. John Stevens told a story about Michael Hickey, who rode the ferry daily to Boom Island. Hickey decided to stop at a St. Anthony saloon to bring a bottle of whisky home for the weekend. Stevens wrote, “The whisky was purchased, paid for, and deposited in his pocket. The saloon-keeper treated Mike for calling on him. Then Mike treated the saloon-keeper and drank, himself, on the occasion. Others came in just at that time. Mike treated them and they treated Mike. By midnight Mike was full and en route for his home over the river. On arriving at the ferry, he found that Captain Tapper had retired for the night. He knew of no reason why he should not take one of the captain’s small boats and ferry himself over the river. He launched the boat, but instead of making the west-side landing, he was carried over the Falls. Early next morning a band of Winnebago Indians in making the portage of the Falls, discovered a white man, or his ghost, on Spirit Island. They immediately informed Mr. Northrup and myself of their discovery. Captain Tapper had just informed me that someone had stolen one of his boats during the night. We sent for the captain, and all three proceeded down to the Falls. There stood Mike on the bank of Spirit Island, without a blemish.”

In 1851 Tapper ran an advertisement in the St. Anthony Express: “Capt. John Tapper is prepared to convey the traveling public across the Mississippi in his unrivaled ferry boat … . The captain will always be in attendance at the sound of the horn which can at all times be found in his boat.”

Second ferry line

With the ferry line up and running, Tapper decided to build another one upstream, at the now-vacant lot at 1812 Marshall St. NE. The ferry crossed the river from Marshall to 26th Avenue N.

In 1856, a house was built on the lot that was owned by Richard Chute, an early Minneapolis real estate speculator, for whom Chute Square is named. The house became the home of the ferry operator.

It was a small house, just one and a half stories, “with a wing flung out for a kitchen,” according to a 1939 Minneapolis Star-Journal article. It was clad in gray shingles and “backed right up to the river.”

Chute sold the house to Judge James Gilfillan, who went on to become Chief Justice of the Minnesota Supreme Court. Gilfillan rented it out for a while, then sold it to the father of Lawrence Galka, who was photographed in front of it in 1939.

The ferry business was short-lived. The Hennepin Ave. Bridge was built in 1855, the first bridge to span the Mississippi. It was a toll bridge, and Tapper became the tollkeeper.

His legendary tight-fistedness came to the fore. General C.C. Andrews, Minnesota’s first chief fire warden, experienced this firsthand. He paid his 5 cents to cross the bridge and was allowed to pass. Later, when he returned, he had to pay again. “But I paid once,” the general said. “Do I have to pay to go back?”

Tapper replied, “Young man, there is no going back in this country.”

The Nicollet Island ferry shut down with the arrival of the bridge. The ferry on Marshall St. continued to operate for a few more years. Tapper moved to Iowa, then northern Minnesota, where he died in 1909. A statue of him once graced the downtown Minneapolis Public Library; it later disappeared. He was, for a time, memorialized when the Island Sash and Door Company opened as the Nicollet Island Inn in 1982. A ground-floor pub was named after him; the space was later converted into a banquet area.

The house was condemned and fell to the wrecking ball in 1969. The land reverted back to Hennepin County as tax-forfeited property. In 2008, the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board purchased the empty lot.

Sources:

“80-Year-old Ferry House on River Keeping Up With the Times—Has Its ‘Face’ Lifted, Minneapolis Star-Journal, Sept. 3, 1939

“Island Sash and Door Converted to 24-Room Hotel”, Northeaster, July 24, 1982

Northeaster, May 18, 1988, p. 9 photo caption

Leonard, Dr. William E., “Early Days in Minneapolis,” Library of Congress, 1914, memory.loc.gov

Atwater, Isaac, History of the City Minneapolis, Minnesota, Munsell, 1893

Holcombe, R.I. and Bingham, William, Compendium of History and Biography of Minneapolis and Hennepin County, Minnesota, Henry Taylor & Co., Chicago, 1914

Neill, Rev. Edward D., and Williams, J. Fletcher, History of Hennepin County and the City of Minneapolis, North Star Publishing Company, Minneapolis, 1881

Parsons, Ernest Dudley, The Story of Minneapolis, Colwell Press, 1913

Stevens, John, Personal Reflections of Minnesota and Its People, 1890

Writers’ Program of the Works Progress Administration, Minneapolis, the Story of a City, Minnesota Department of Education and Minneapolis Board of Education, 1940

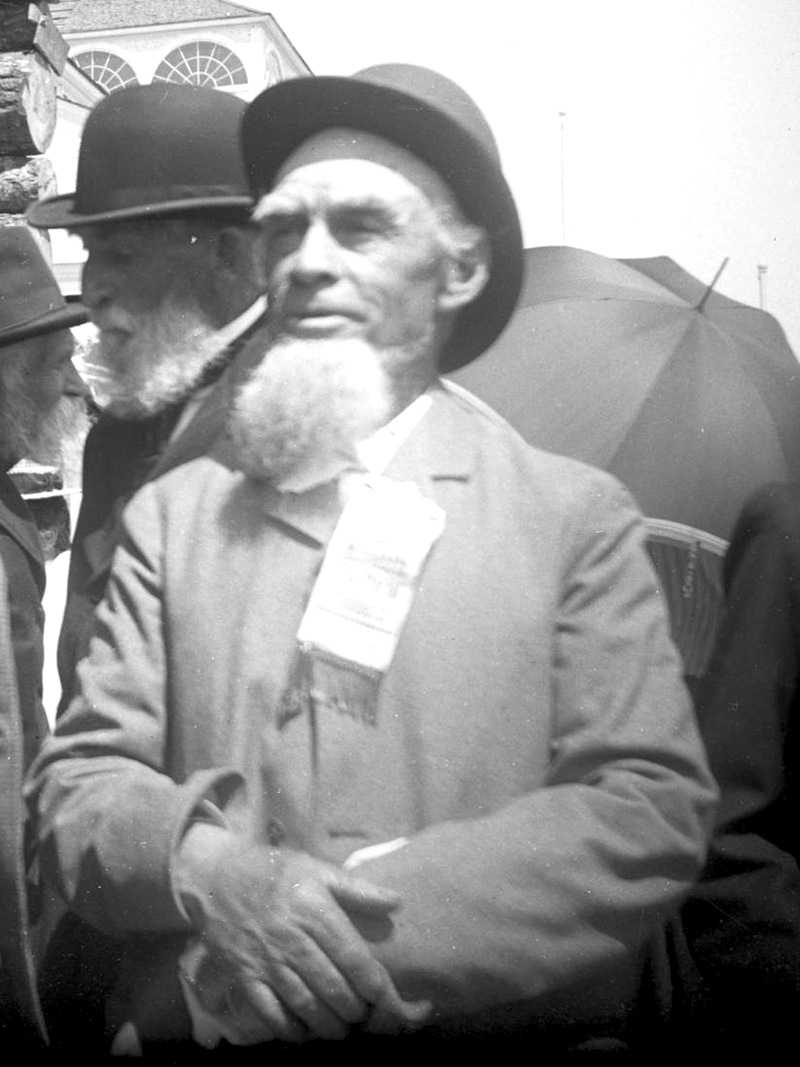

Captain John Tapper (Hennepin County Library)

Lawrence Galka in front of the ferry house at 1812 Marshall St. NE in 1939. (Minnesota Historical Society microfilm)

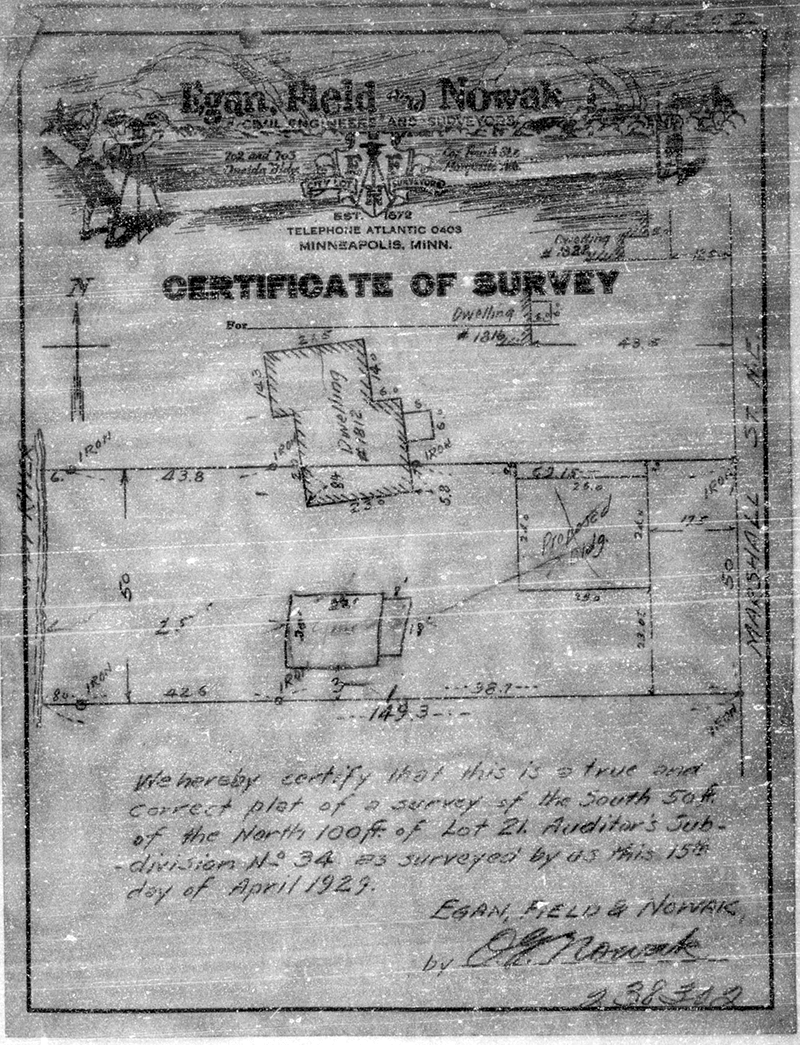

A 1929 survey map shows the orientation of the ferry house on the lot. Other buildings were proposed for the property. Marshall Street is on the right. (Hennepin County Library)

Are these mortared limestone bricks part of the ferry house chimney? (Cynthia Sowden)