In 1857, William P. Washburn established a furniture store at the corner of Central Ave. and 4th Street SE. It was common then for furniture stores to also make and sell coffins and provide undertaking services. As Minneapolis grew, so did its funeral industry. Washburn soon shifted his business to undertaking. By the turn of the century, there were 21 undertakers in Minneapolis.

At one time, there were six funeral homes in Northeast, including what eventually became Washburn-McReavy. O.E. Larson, a Swedish immigrant, started his business on 19th and Central in 1895. Joseph Kozlak opened on University Ave. in 1908. Samuel Billman started his Central Ave. chapel in 1917. The Rainville family, who had operated a furniture store on Nicollet Island, opened a funeral chapel on East Hennepin in 1928. Stanley Kapala started offering undertaking services on 10th and Main in 1932.

Just 25 years after Washburn started his business, four Minneapolis businessmen – George S. Spaulding, Melvin R. Ellis, George W. Bailey and Israel W. Cone – formed Northwestern Casket Company in 1882.

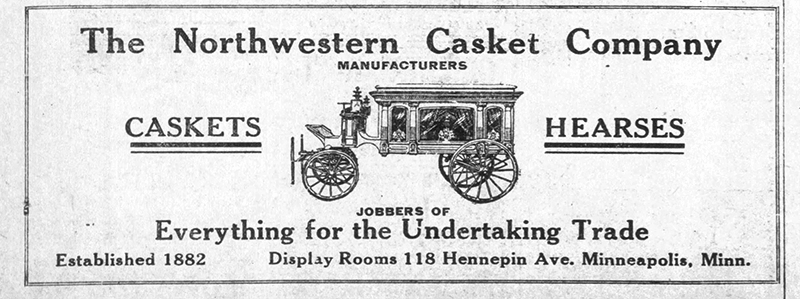

Northwestern Casket began building caskets in a plant on 8th St. and 8th Ave. SE, but quickly outgrew the space. A new building was erected in Northeast. With a showroom downtown, and a factory on 17th and Jefferson, the company was on its way to becoming regional supplier of funerary goods.

The plant was sustainable. According to a company history presented to University of Minnesota mortuary science students, “In the 1880s, when their doors first opened, the business was completely self-sustaining … Con [Conrad Nelson, chief engineer] set up the system of burning scrap lumber and sawdust along with coal to make steam in the high-pressure boiler. The live steam drove a steam engine, the steam engine drove a generator which made the electricity to operate the plant. The exhaust steam from the engine was used to heat the building and dry lumber in the kilns. The coal was brought in by boxcars on a track that came right up to the building, dumping it into a long coal bin that still exists today.”

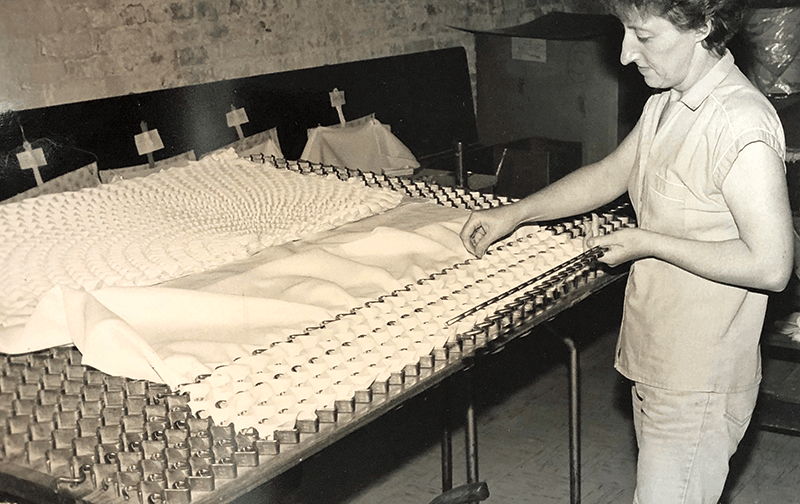

Skilled cabinetmakers fashioned the caskets, which had replaced coffins in popularity. (Coffins have six sides and have a “human” shape; caskets are rectangular.) Blacksmiths created the “furniture” – metal handles, hinges and locks. The company also employed seamstresses to sew the elaborate satin linings and pillows for the caskets. Hearses were soon added to the line.

Shipments of raw lumber arrived daily at the plant where craftsman created and assembled the casket shell and customized the interior fabric. Caskets were ordered by funeral directors via express telegraph or U.S. Postal Service and shipped by train to the funeral provider.

Northwestern Casket marketed its funeral supplies to undertakers via a catalog. They could order not only caskets and hearses, but other funeral supplies, such as burial garments and burial vaults. In 1915, a walnut casket with a hinged lid cost $55 – for the box. If you wanted a velour interior, it cost $4 extra.

The Minneapolis Tribune noted the company had an annual output of $375,000 worth of caskets and hearses in 1912 ($11.4 million in today’s dollars). In 1914, Northwestern Casket was the largest casket manufacturer in Minneapolis. “The firm sends caskets all over the Northwest and beyond the regular business territory of Minneapolis,” the Tribune reported in an article about East Minneapolis industries.

Northwestern Casket was a leader in other ways, hosting seminars for those in the funeral trade. One such “school” took place at the factory in 1888. An article in the Minneapolis Tribune, “Undertakers Entertained,” (with the unappetizing subheading of “The Embalming School Closed with a Banquet Yesterday”), detailed a two-day session attended by 70 undertakers from across the state. “After a few preliminary remarks Friday morning, the instructions given in the lectures were made still more impressive by practical demonstration,” the paper reported.

A fire broke out in the downtown showroom at 118-120 Hennepin Ave. in 1919. “More than 900 men, women and children, guests at six hotels in the Gateway [near the Hennepin Ave. Bridge], fled to the street in their night clothing at 11:30 last night,” reported the Minneapolis Tribune. President M.C. Williams estimated the casket company’s losses at $20,000 to $25,000. They included “ten hearses, hundreds of caskets and funeral fittings.”

The company history relates, “In the 1930s and ’40s the business employed 100 people. Most of them were from the Northeast area. They walked to work or rode the trolleys. Stanley Czaja was employed from 1925 to 1972. He became mill foreman in 1942. He spoke fluent Polish, so the company was able to hire many displaced persons from Europe after World War II because Stan could communicate with them.”

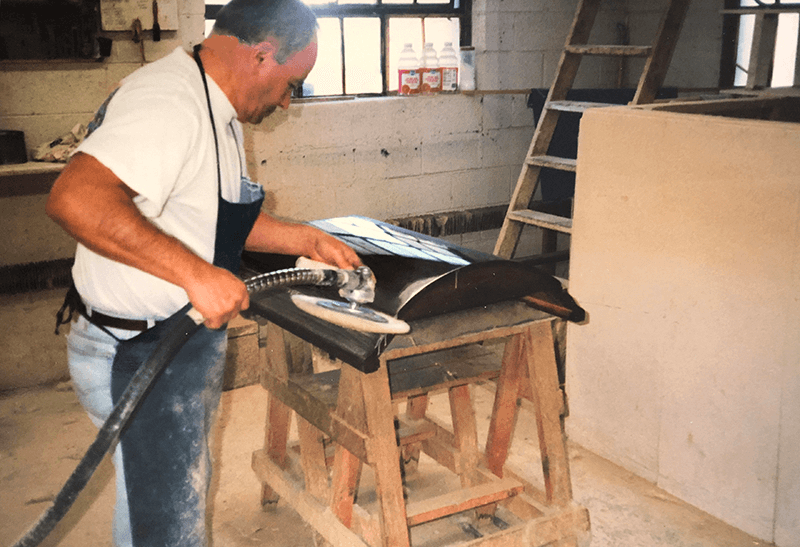

Northwestern Casket continued to build caskets well into the 1960s and ’70s, but times were changing. Skilled cabinetmakers were harder to find. And as more and more families opted for cremation, the demand for caskets slowed. The company shifted its focus from building to customization, a service they took with them when they moved to New Hope in 2006.

Today your funeral director can order a casket in any color, including Minnesota Vikings purple if you’re a fan. Caskets can be further personalized with camouflage liners for hunters, embroidered panels for veterans or golf ball handles if you’re a golf fanatic. Children’s caskets are often accompanied by a stuffed animal. They also sell caskets made without metal parts for Orthodox Jews and Hmong people. With Americans becoming larger and larger, they can also provide a casket 16.5 inches wider than normal and capable of holding 1,000 lbs.

New life in an old building

The old factory didn’t sit empty for long. Jennifer Young and John Kremer bought the building and its accompanying carriage house in the spring of 2006 with the idea of providing work space for artists. With its high ceilings, wood floors and exposed brick walls, it provided plenty of room for studio photography as well as painting and sculpture. They opened the following year. With a nod to the past, they renamed the building Casket Arts.

Sources

“Undertakers Entertained,” Minneapolis Tribune, Jan. 29, 1888

“Important Market for Undertakers,” Minneapolis Journal, March 31, 1910

“East Minneapolis Industries,” Minneapolis Tribune, April 12, 1914

“Fire Menaces 6 Hotels, 900 Lodgers Flee,” Minneapolis Tribune, Aug. 15, 1919

“Church, Civic Worker Dead,” Minneapolis Star, Nov. 20, 1931

Olson, Gail, “Northeast’s changing funeral home business,” Northeaster, July 25 and Aug. 2, 2002

Svitak Dean, Lee, “Supersized items become a growth industry,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, Feb. 8, 2004

Minneapolis City Directory, 1900

Northwestern Casket Company archives

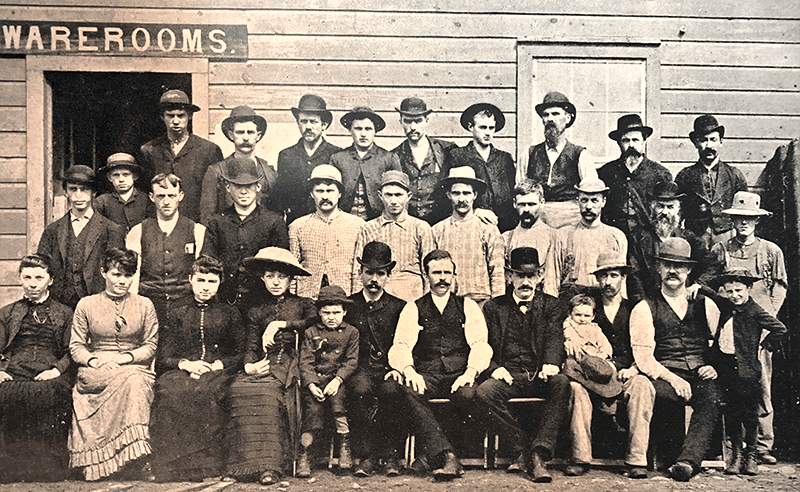

The first Northwestern Casket employees at their location in Southeast Minneapolis, in 1886. A 1914 Minneapolis Journal ad for Northwestern Casket Co. caskets and hearses.Employee polishing a casket top, 1997. In the 1960s, an employee shirred fabric for a casket liner. The form is still used today. (Photos courtesy of Northwestern Casket Company)