The equipment may come from the Hillbilly Stills factory in Kentucky, but don’t call Brother Justus whiskey “moonshine.”

The four-year-old distillery on Taft Street NE produces single-malt American whiskey using both traditional techniques and modern technology. Founder Phil Steger said he decided to create a Minnesota whiskey company around ten years ago, when he and his wife visited a bourbon distillery outside Louisville, KY.

“I was inspired by the realization that whiskey is literally the essence of beer and by the fact that whiskey gets its amber color and caramel/butterscotch flavors from the sugars in oak. I was also inspired by the community that craft a distillery creates—farmers, builders, brewers, distillers, coopers, glassmakers, designers. It also struck me how much the wooded hills and grain-filled valleys surrounding the distillery in Kentucky reminded me of the area around St. John’s University in central Minnesota, where I went to college.”

He added that there was really no reason Minnesota shouldn’t have a great whiskey tradition, given the availability of water, oak, brewing skill, and the support for local craft.

With that thought in mind, Steger educated himself on whiskey-making and its market. The 2011 passage of Minnesota’s “Surly Bill,” which allows breweries to sell their own beer in tap rooms, helped create openings for local distilleries.

Steger got seed money from friends from St. John’s. After that, small and large investors contacted him, mostly through personal relationships.

Four years ago, Steger, with help from Jeremy Blankenship and later James Jefferson, established the Brother Justus Whiskey Company. Jefferson is the head distiller and director of production. He developed the 100 percent barley distiller’s beer recipe, the foundation of the single malt whiskey. The business set up production in a basement space in the Strong Scott building.

Last November, the group locked in their recipe and technique, after three years of effort. They launched their website and activated a Facebook page. After hanging up an outdoor sign, they opened to the public the week before Christmas.

Steger said, “We worked with a number of different local contractors to build out the plumbing and the electrical and install a boiler and our steam-jacketed still. We worked with interior designer Jacqueline Fortier and a designer from the Guthrie, Kellie Larson, who both did great work helping make our small underground distillery and tasting room tell our story.”

The open subterranean space is lit by west-facing windows. Below the windows are a copper still and stainless steel containers, hot-water heaters, and a steam boiler. Next to those is kitchen-like area, with a table and a gurney covered with bottles and testing equipment.

Some of the equipment is hidden behind a dark curtain, the background for a small bar, large enough for four people to rest their elbows on. Fabricated by furniture maker Mitch Sondreal, the bar has a copper surface and a surround made from the same charred oak as the whiskey barrels.

About fifty of the 6.2-gallon oak barrels are stacked on either side of the bar. Above the barrels is a shelf holding a half-dozen stoneware whiskey jugs. Across the room is a tasting area, with an oak table and four overstuffed chairs, and a small room for retail bottle sales.

By law, the sales room must be technically separate from the distillery. A sign near the door reads: “Minnesota liquor laws limit distillery sales to one (1) 375 ML bottle per customer per day.” Steger, by day an attorney with Dorsey & Whitney, makes sure everything’s in compliance.

Painted wall graphics depict Brother Justus, a Benedictine monk at St. John’s. The monk built free (albeit illegal) whiskey stills for local farmers, so they could make moonshine to support themselves and their families during Prohibition.

Jefferson described the distillation process: “Whiskey begins with beer; to mak beer you combine the barley with hot water to make the sugar that you can ferment. For our still we use a steam-jacketed kettle, and we use a hot-water boiler to make steam to heat the kettle.

“We extract the sugars from the malted barley into a liquid form, and ferment that into what is called “distiller’s beer.” That beer ferments for a few days until it creates the alcohol, then it’s pumped into our still where it’s heated until the alcohol evaporates.

“As the vapor rises up the column, we ‘rectify’ it, to get it to the right proof and flavor we want, and at the very top, we hit it with a chiller, which turns it into a liquid, and it flows out a pipe.

“A lot of things can evaporate from the liquid as that whole cloud of chemicals gets up to the top [of the column]. When we’re ready, we check the proof with a hydrometer, to control the quality of the product.”

Jefferson concluded, “God bless the fact that we live in a world where alcohol boils at a lower temperature than water; it’s the only thing that makes all this possible.” Steger describes it thusly: “We make malted barley into a cloud that rains whiskey.”

The liquid is 90+ percent alcohol, which is then cut in half with distilled water, at which point it’s put into barrels and the aging begins. Jefferson said that because of the purity of the ingredients, four months’ aging in charred oak is sufficient.

Steger said they have been building up an inventory that, based on sales estimates, “will make sure we never run out of whiskey.” When that inventory is ready, Brother Justus will hold a grand opening, planned for June 9.

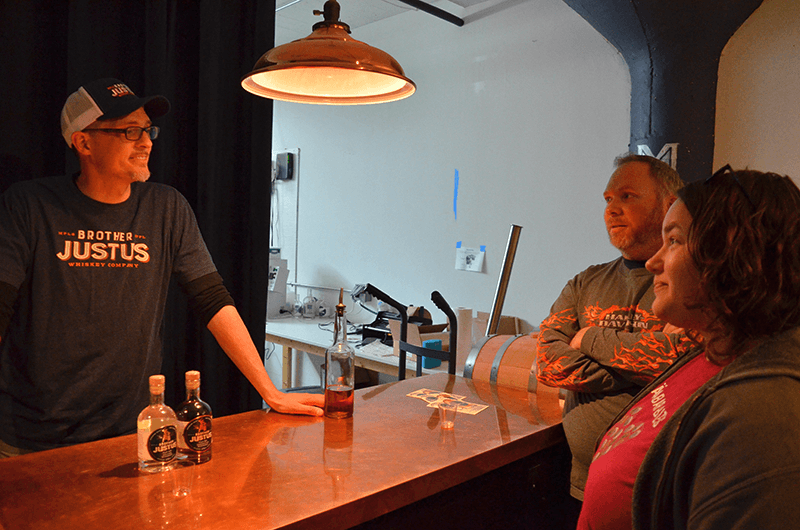

Below: Founder Phil Steger (left) talks with some tasters at the taproom. (Photo by Mark Peterson)