What will Minneapolis be like in 2040? Will trolley cars have made their comeback? Will the skyline be cluttered with high-rises? Will anyone be able to afford to live here?

A Dec. 2 open house at Van Cleve Park left participants with more questions than answers.

The open houses are the second phase of a five-part sequence of events designed to get residents’ feedback on Minneapolis’ comprehensive plan, known as Minneapolis 2040. The effort launched in January 2016. The first three months were spent exploring ideas and trends and identifying a list of topics or “big questions” to bring before the public. Those 15 topics were brought to the fore in October 2016.

Between November 2016 and September 2017, the Minneapolis Department of Community Planning and Economic Development (CPED) drafted policies for areas including land use; livable and resilient communities; housing; urban design and development; transportation; environmental systems; public health; parks and open spaces; heritage preservation; arts and culture; economic development and competitiveness; public services and facilities; human capital, engagement and education; technology and innovation; and governance, intergovernmental relations and partnerships.

Taking it to the people

This past summer, CPED began working with neighborhood groups to gather feedback on its draft proposals.

The large meeting room at Van Cleve was set up like an information fair, with various “booths” scattered around the perimeter. As people entered the room, they were given stars and asked to mark their home’s location on a map of the city. The meeting was sponsored by the Marcy-Holmes and Waite Park neighborhoods, and a good number of stars represented those areas as well as other parts of the city. CPED’s Paul Mogush is principal coordinator of the Minneapolis 2040 project. He said at least 15 city planners have been available at each of the open houses. “We’re trying to give people a first look at policy directions,” he said.

How we got here

One of the booths took a look at housing policies of the past, specifically, racial covenants. Racial covenants were deeds that were used to prevent people who were not white from purchasing or occupying property. They were in effect in Minneapolis from 1910 to 1968. One of the highlights of the exhibit was a map produced by the Mapping Prejudice Project, which has identified more than 5,000 lots in Minneapolis that once had racial restrictions on them. Restrictive racial covenants began on the city’s south side. The first such covenants appeared in Northeast in the late 1920s on the far eastern edges of the Audubon and Windom Park neighborhoods. (See mappingprejudice.org.)

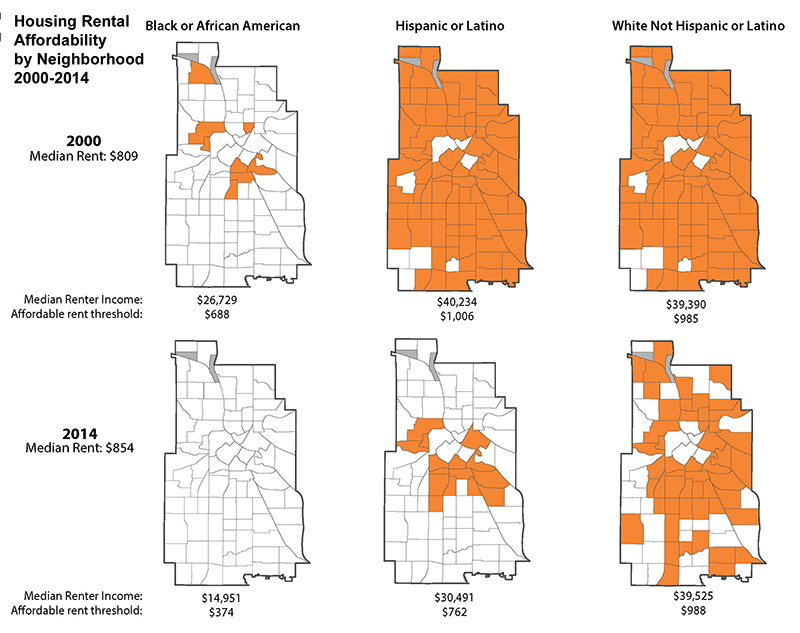

An analysis done by the University of Minnesota’s Center for Urban and Regional Affairs (CURA) showed that rents increased to unaffordable levels between 2000 and 2014, while at the same time income has declined or remained stagnant, depending on the group. In 2000, median income for blacks was $26,729; their “affordable rent threshold” (the point at which a family can afford 50 percent of the housing units in their neighborhood) was $688 per month. Median rent was $809. In 2014, median income had plummeted to $14,951 and the rental threshold was $374. However, median rents were $854.

Hispanics or Latinos also underwent a decline in income and purchasing power in the 14-year period. In 2000, median income was $40,234, and a family could afford $1,006 in monthly rent. By 2014, median income had declined to $30,491, and the affordable rent threshold was $762.

White Minneapolitans were not left out of this trend, as parts of the city became less affordable to them. However, they didn’t make much progress. Median income was $39,390 in 2000, and the rent threshold was $985. By 2014, median income had increased only a little, to $39,525, and the rent threshold was $988.

Providing feedback

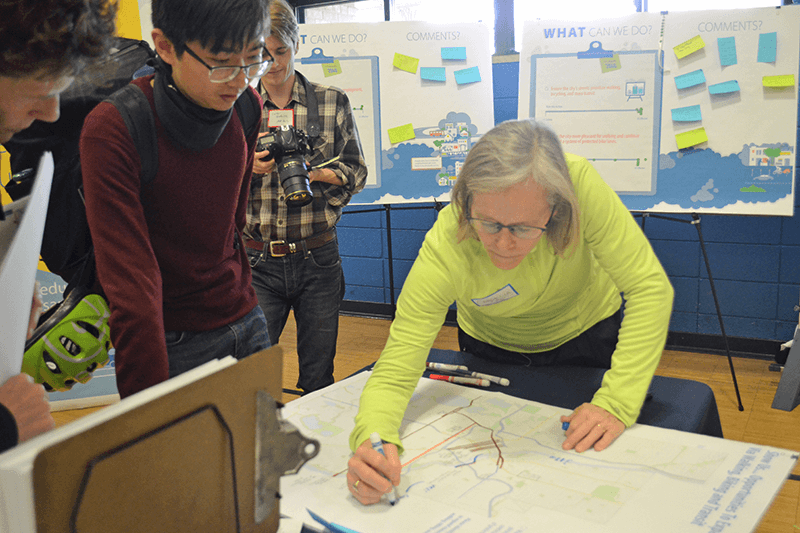

At other tables, participants were asked to draw their ideas about transit on a map, showing the current bus/LRT system and where they’d like to see connections in the future. Currently, nine out of 10 trips across the city are taken in personal automobiles. To meet the city’s climate goals for 2040, car trips need to be reduced by at least 40 percent. A more convenient transit system would help reach that goal.

At other stations, participants placed dots along a continuum, indicating whether they felt the city was making progress in a certain area, such as providing access to retail (being able to buy groceries without having to drive to a store). At each open house, participants have also heard, “This is what you’ve told us” from CPED staffers.

Mogush said a draft of the plan will be available for public comment beginning in March and running through May. CPED will take those comments into consideration as it produces a final draft of the comprehensive plan and presents it to the City Council in the fall of 2018, and the Metropolitan Council by the end of the year.

You still have time to weigh in on Minneapolis 2040. You can take the online survey at minneapolis2040.com. You can also attend an additional open house scheduled for Jan. 23 at Plymouth Congregational Church, 1900 Nicollet Ave., from 6-8:30 p.m.

The “Big 15” — Minneapolis 2040’s 15 areas of concern:

• Land Use: Detailed policies about the location and characteristics of housing, commerce, and parks that will guide how the city will grow and change through 2040.

• Complete Livable and Resilient Communities: Tying multiple policies together to plan for livable communities where people can meet their daily needs without excessive travel, and that are resilient in the face of climate change.

• Housing: Guiding housing supply, choice, maintenance, quality, and affordability.

• Urban Design and Development: Policies guiding the design of buildings, public spaces, signage, and infrastructure.

• Transportation: Providing accessibility to destinations via all modes of transportation, including walking, biking, driving, and public transportation.

• Environmental Systems: Managing environmental systems and impacts, including city operations, water resources, waste management and recycling, air quality, noise, brownfields cleanup, and energy.

• Public Health: Promoting active living, emergency preparedness, environmental health, food and nutrition, health and human services, social cohesion, and mental health.

• Parks and Open Space: Focusing on green spaces and facilities not owned and operated by the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board.

• Heritage Preservation: Protecting and reusing culturally significant features of the built and natural environment, including buildings, districts, landscapes, and other historic resources.

• Arts and Culture: The contributions of arts and culture to a vibrant and livable city.

• Economic Development and Competitiveness: Guiding the economic competitiveness of our city and region, focusing on the city’s businesses, workforce, industrial districts, and Downtown.

• Public Services and Facilities: The siting of publicly-owned buildings, planning for public facility needs, public safety, and inspections and licensing.

• Human Capital, Engagement and Education: Supporting and engaging people in the city, including community outreach, education, social services, equal access, civil rights, and customer service.

• Technology and Innovation: Advancing the use of technology to improve City services and on fostering technology-based economic development.

• Governance, Intergovernmental Relations and Partnerships: Implementing the policies of the comprehensive plan through work with other public agencies.

Below: Chart: All across Minneapolis, people’s ability to pay rent at certain income levels has declined. The need for affordable housing affects all races. (Graphic courtesy of CPED)

Photo: Participants drew lines on a transit map to show where they think improvements are most needed. (Photo by Cynthia Sowden)