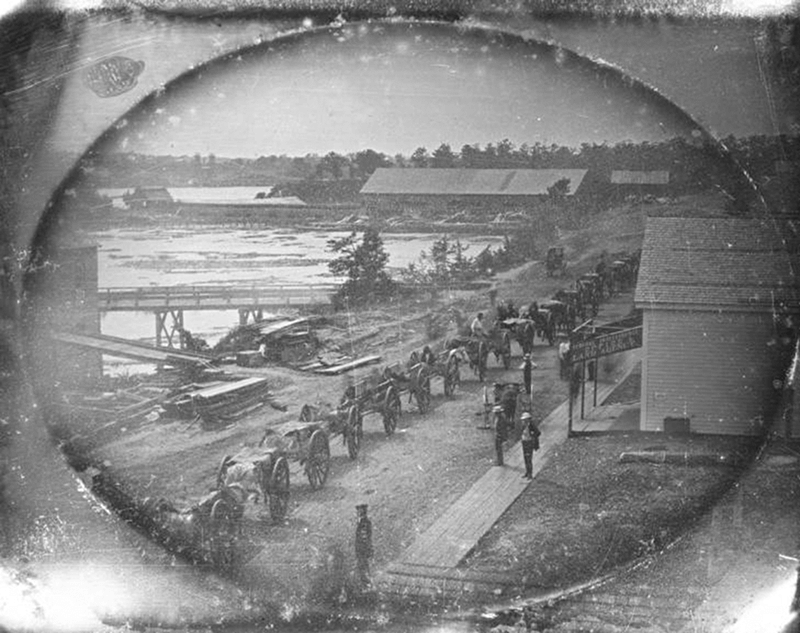

It’s been 200 years since oxcart trains rumbled down Marshall Street on their way to Main Street and farther east along University Avenue into St. Paul, but they played a major role in building the early economy of Minnesota, and helped shape Northeast Minneapolis. Although the wheel ruts have long since been paved over, the route that ran from Red River (Winnipeg, Manitoba) to St. Paul can still be traced.

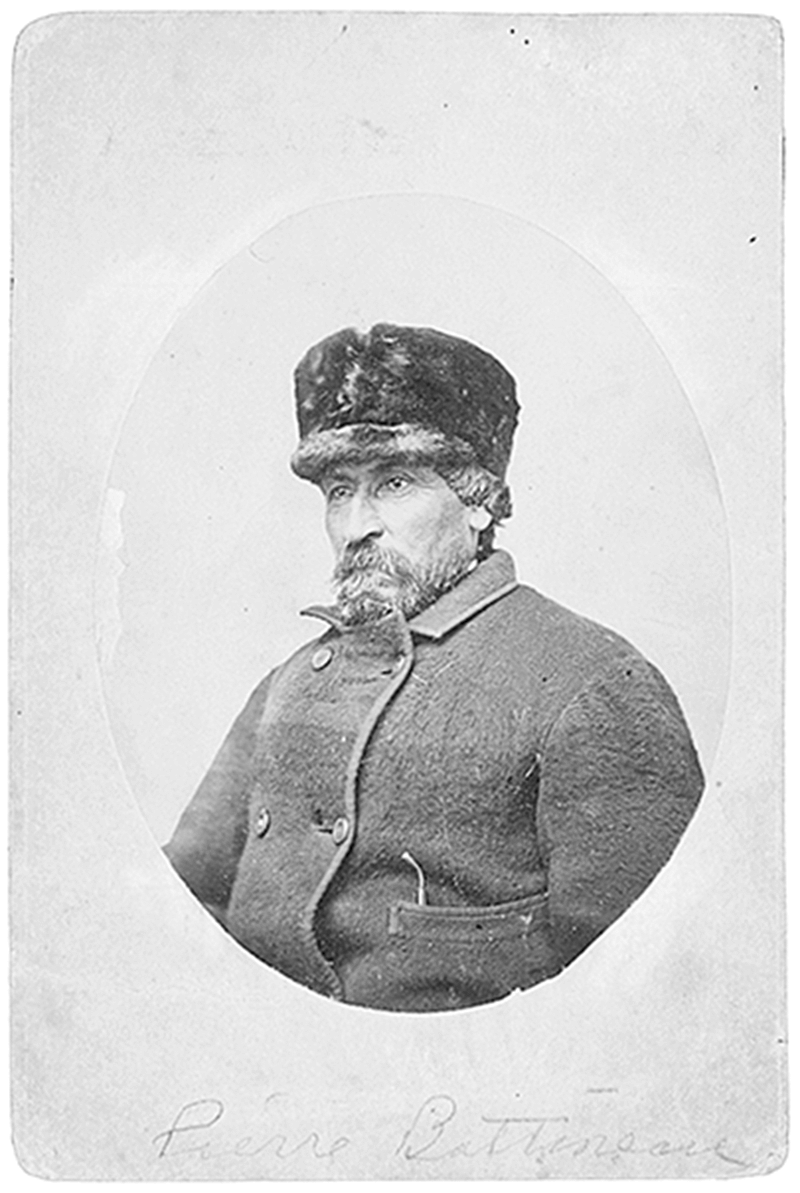

The Red River oxcart trails were used by independent fur traders seeking a faster route to market and a better deal than they received from the Hudson’s Bay Company, which monopolized North American fur trade. Many of the independent traders were Métis, descendants of French Canadian fur trappers and Ojibwe women. They lived with their feet in both the white and Native worlds, speaking a mélange of French, Ojibwe and English, doing some farming, but mostly trapping and hunting buffalo along the Red River of the North. One trader had a familiar name in Northeast: Pierre Bottineau.

Two major trails came down from Canada. One followed the Red River down what is now the Minnesota-Dakotas border to the Minnesota River and Ft. Snelling. The other cut overland through central Minnesota to St. Cloud and followed the Mississippi River through the new settlement of St. Anthony. Today, if you drive down I-94 from Alexandria, exit at St. Cloud and drive down Hwy. 10 into Minneapolis, you’re roughly following the Red River Trail.

The two-wheeled carts that bore 800-1,000-lb. loads of furs and buffalo hides from the northern prairies were made of two materials – wood and buffalo hide. The five-foot-high wheels were originally flat wooden circles, but spoked wheels soon replaced them. Nails were precious and expensive, so the traders used strips of buffalo hide soaked in water to bind the wheel pieces together. As the “babiche” dried, it shrink-wrapped the wheels. Axles were made of single logs. If one broke along the way, the men would simply cut down a tree to replace it. The wheels were dish-shaped, like a contact lens. Although they looked rickety, their shape helped them move across uneven and slippery roads. The wheel hubs were not lubricated because the combination of grease and prairie dust soon made them immobile. When the Métis traveled in caravans of 200 or more, the squeaking wheels could be heard for miles.

Northwestern Minnesota is pock-marked with watery potholes and marshes, but the Métis had ways of getting around or through them.

William Gomez da Fonseca made several trips on the trail in the 1860s. He described how the trains forded swollen streams: “Four cart wheels were taken and placed dish upwards and the four points of contact securely fashioned together. On the outer rims four pieces of wood were lashed forming a square. Meanwhile six buffalo hides were soaked, when sufficiently soft sewed together, and spread out, upon which the frame was placed. The edges were brought up and laced to the outer bars, one line fastened to the stern, the other to the bow. A party would then swim across, carrying the bow line over; the boat was launched and floated like a duck.”

At other times, the men cut trees and built a corduroy road to get across the areas they called “traverses.” They also braided logs of tall prairie grasses and threw them down for the oxen to walk on.

Driving a loaded oxcart 500 miles across the unmarked prairie was intense. The land the traders passed through was in dispute between the Dakota and the Ojibwe, and no one had asked their permission to cross. When not battling the elements or Natives, they fought off mosquitoes which rose from the earth in black clouds in the evenings. They made an average of eight to 15 miles per day.

Their diet consisted of pemmican – ground, dried buffalo meat mixed with fat and berries – and flour and black tea as well as game and fish they took along the way. The pemmican was packed in 90-lb. bags.

Women and families often accompanied the traders. In 1923, Harriet Goldsmith Sinclair Cowan recalled a trip she made in 1848. “We were three weeks traveling across the plains to St. Paul. We had three Red River carts with horses and a force of six men. The carts were without springs, of course, but with our bedding comfortably arranged in them, they did not jolt us so badly, except where the ground was very rough, and then we could get out and walk.” She saw Pierre Bottineau’s house in St. Anthony on that trip. It was the second frame house built in the city.

Bottineau had traveled the trail since 1837, bringing furs and hides to St. Paul and backhauling goods to Red River. He was an in-demand guide and was often asked to escort expeditions west of the Mississippi. Over six feet tall and weighing more than 200 lbs., he was fluent in French, English, Dakota, Ojibwe, Cree, Mandan and Winnebago and often worked as an interpreter. Despite being illiterate (he signed documents with an X), he bought and sold property from St. Paul to the Canadian border. He once owned part of Nicollet Island, but lost it in a card game. His home in St. Anthony was “party central” when the Red River men came to town.

In 1904, Frank G. O’Brien described their arrival. “The squeaking of the wheels … was a signal for all the young people, and the old ones as well, living in the pioneer settlements along the route, to be on hand to see the Red River carts as they passed through town. I remember having heard them many a time in the summer mornings in the settlement of St. Anthony. They camped a few miles out where the grazing was good and water near by [sic], and would reach town about sunrise, arousing us from early morning slumbers, to watch them move along mechanically at a snail-like pace. The value of their loads amounted in the aggregate to many thousand dollars.”

With their blousy shirts, colorful sashes, wide-brimmed hats and dark complexions, the Métis seemed exotic to St. Anthony residents. One woman chained her dog outside her home to keep them away. Another recalled a preacher who quickly wrapped up his sermon when he heard the carts’ squeaking wheels. They were, perhaps, more welcome in St. Paul, where they freely spent the money they received for their goods.

The fur trade started to dwindle in the 1860s. By 1870, agriculture powered the state. Roads had improved, and railroads had taken the place of the Red River Trail. The man who guided railroad magnate James J. Hill to the best route from St. Paul to Winnipeg was Pierre Bottineau.

Sources:

Compendium of History and Biography of Central and Northern Minnesota, George A. Ogle & Co., Chicago, 1904

Gilman, Rhoda R., Gilman, Carolyn, and Stultz, Deborah M., The Red River Trails: Oxcart Routes Between St. Paul and the Selkirk Settlement, 1820-1870, Minnesota Historical Society, 1979

Healy, W. J., Women of Red River, Being a Book Written from the Recollections of Women Surviving from the Red River Era, The Women’s Canadian Club, 1923

Nute, Grace Lee, “New Light on Red River Valley History,” Minnesota Historical Society address, June 21, 1924

O’Brien, Frank G., Minnesota Pioneer Sketches: From the Preserved Recollections and Observations of a Pioneer Resident, Housekeeper Press, 1904

Stone, Tom, The Legend of Pierre Bottineau and the Red River Trail, Eschia Books, Canada, 2013

Below: A line of Red River oxcarts rolls down Main Street in St. Anthony in the 1850s. Photo by Edward Bromley (Hennepin County Library) Pierre Bottineau (Minnesota Historical Society)