Mention the word “quarry” nowadays and you’re apt to get directions to a certain shopping center just south of 18th and Johnson. But just 100 years ago, there were several quarries in Northeast. They formed a belt around the southern end of the neighborhood and provided employment, entertainment and headaches for the neighbors. Their primary product was crushed rock for road construction, what we call “Class 5” today. Automobiles were becoming popular, and Minnesota was in road-building mode.

The quarries

There were six quarries in Northeast in 1918, the year Oliver Bowles published “The Structural and Ornamental Stones of Minnesota” under the auspices of the U.S. Geological Survey.

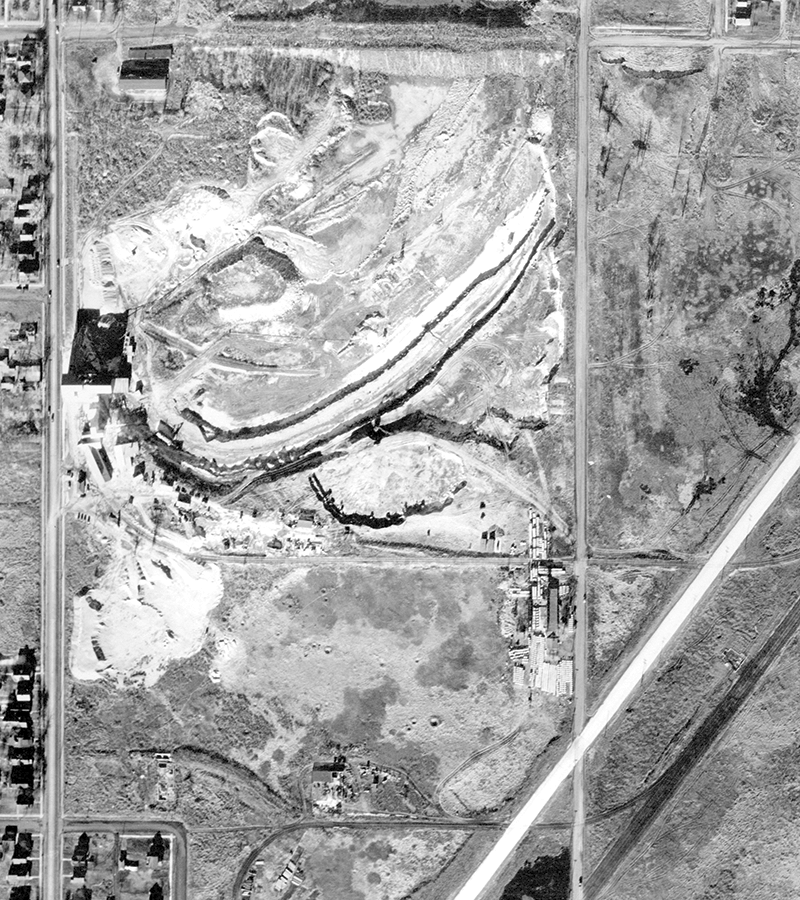

The largest – and later, most infamous – was probably the Minnesota Crushed Stone Company, later known as Gopher Stone. It was started in 1903 by German immigrant John Wunder. The quarry was located on Johnson Street, between 15th and 18th avenues, roughly the freeway area next to the Quarry Shopping Center, and it stretched back to Broadway and K Street (Wilson Street NE).

Minnesota Crushed Stone blasted the thin-bedded yellow limestone with dynamite, then loaded it into dump cars with a steam shovel. The cars hauled it out of the quarry to a crusher Wunder had installed in 1914. Although Wunder basically strip-mined the area, the quarry must have been somewhat pretty, with a 4-foot stripe of yellow on top, followed by 6 feet of blue-gray limestone, and 14 to 18 feet of hard blue limestone on the bottom.

Between Johnson and Central Avenue was the Minneapolis Stone Company at 16th and Fillmore Street, today the location of Sociable Cider Werks. The blue limestone beds on the east side of the quarry were also 14 to 18 feet thick. “The whole output is crushed stone, which is used extensively for concrete and road construction,” wrote Bowles.

The Blue Limestone Company operated on a 10-acre site at the corner of 15th and Central. The company also had a crushing plant near Broadway and K. Blue Limestone furnished concrete materials for the construction of the Nicollet Hotel downtown in 1923.

Bowles lists the A. P. Anderson quarry as “north of the excavation made by the Blue Limestone Co.” He said the quarry produced “excellent quality” rubble for foundations.

L.P. Johnson had a quarry on a 40 x 100-foot lot at 1131 Fourth Street NE. Today, it’s the site of a single family home across the street from Las Estrellas School. Half of the quarry was “worked out,” said Bowles. Johnson supplied rubble for house foundations.

Andrew Rogers ran a similar rubble quarry near the corner of Third Street and 13th Avenue. “Available stone covers an area of about half a city block,” Bowles noted.

Hortenbach opened a quarry at Fifth Avenue and Fifth Street in 1911. By the time Bowles’ book was published, the half-acre strip was about half exhausted. Hortenbach was able to take 10-inch blocks out of the ground; horses powered a derrick that lifted the blocks.

By 1930 when he retired and sold the business, Wunder owned both Gopher Stone and Blue Limestone. The Gopher quarry employed 100 men in the summer when road construction was at its peak.

Dangerous workplaces

Using dynamite to loosen the limestone wasn’t the only danger workers encountered at a quarry.

In 1918, Northeast resident Victor Schold was buried for an hour under a pile of sand at the Blue Limestone gravel works when the ledge of the gravel pit where he and other laborers were working collapsed. “Schold’s fellow workers, after shoveling with desperate speed for a short time in an effort to rescue their companion, called for aid, and squad wagon No. 2 of the fire department, under Captain Andrew Griswold, arrived,” reported the Minneapolis Tribune. It took 30 minutes to extricate Schold, who was “weak from pressure and suffocation.”

The following year, 50-year-old Andrew Johnson, who lived at 1828 Lincoln Street NE, was killed while operating machinery at Minneapolis Stone Company. “He was crushed and mangled and lived only a few seconds,” the Tribune reported.

Swimming holes and tragedies

Quarries were natural catchments for rainwater, and, in an era before wading pools and waterparks were installed in Minneapolis parks, they were popular places to swim. Boys were particularly apt to skinny dip when no one was around.

The Minneapolis Tribune staff appeared to get a chuckle out of a 1921 incident in which six young boys were caught swimming in the quarry pool on 15th and Buchanan in their “smile and freckle suits. They were splashing about happily when prudish policemen, summoned by scandalized housewives of the neighborhood, took them in custody.

“‘This isn’t the Garden of Eden,” Capt. Patrick Queally told the half dozen, ‘and your costumes are good only on Saturday night with the curtains down. Get some clothes on when you go swimming again or the law will put you in pretty suits with stripes running around them.’”

Clothes or no clothes, the swimming holes were a dangerous attraction.

On June 11, 1925, 11-year-old Charles Wyckhoff, 2535 Buchanan Street, drowned at the Minneapolis Stone Company quarry, which had been abandoned. In April 1928, 9-year-old Hugo Roos fell into the pit. Despite the efforts of his playmate Edwin Hegsted, who found a length of wire, fastened it to a tree and tossed it to him, Hugo drowned. According to the Minneapolis Star, the pond was about a block long and 20 feet deep.

Parents throughout Northeast were outraged. The city could not find the quarry’s owner, and Hennepin County Commissioner A.R. Ferrin said property taxes were unpaid. The Edison PTA began a campaign to raise money to put a fence around the quarry. The Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board acquired the land in 1941; it became the basis for Northeast Athletic Field Park.

Another tragedy was avoided in 1921, when workers found a baby girl wandering around one of the quarries. Old enough to say “mamma” and “daddy,” but unable to give her name, she was thought to be abandoned. Police took her into their care.

Neighborhood nuisance

The quarries, especially Minnesota Crushed Stone, were not beloved by the neighbors. They claimed in one newspaper account that blasts at the quarry broke windows and “scattered fine dust in their food.”

In 1918, Gust and Emma Ehlin, who lived at 1826 Johnson Street, filed suit against Minnesota Crushed Stone. They were joined by 28 others who sought an injunction to prevent the company from further rock quarrying, the Minneapolis Tribune reported. “The noise and smoke of the operations, they alleged, made life at home almost unbearable and decreased the value of the property.” The Ehlins sought damages of $3,500. The first judge refused the injunction. The Ehlins tried again in 1919, and the judge ruled in favor of the company. The Minnesota Supreme Court sent the case back to the lower court to gather evidence that quarry operations could be quieter. Undeterred, the couple tried again in 1921, with a bench hearing. The Northeaster was unable to determine whether the Ehlins received a settlement. Mrs. Alice Millett, 1831 Johnson, received $1,932 in damages but had to give it back when she couldn’t prove she owned the property at that address.

The end of quarrying in Northeast

The quarries petered out, one by one, as the veins of Platteville limestone were transferred to roadbeds and the holes were filled in. The quarry at 15th and Johnson continued to operate for a time, but was shut down by the 1960s. When construction of 35W began in the ‘70s, much of the excavating had already been done.

Sources

Bowles, Oliver, “The Structural and Ornamental Stones of Minnesota,” U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 663, Washington, DC, 1918

“Three Building Shifts Assigned to Construction,” Minneapolis Sunday Tribune, Aug. 26, 1923

“Buried for Hour Under Sand Pile, Workman Lives,” Minneapolis Sunday Tribune, Dec. 8, 1918

“Sand Quarry Workman Crushed in Machinery,” Minneapolis Tribune, June 25, 1919

“Grins and Freckles Are Banned as Costume for the Small Boy Brother,” Minneapolis Sunday Tribune, May 22, 1921

“Second Youth Drowns in Old Stone Quarry,” Minneapolis Star, April 11, 1928

“Edison P.T.A. to Fence Old Quarry,” Minneapolis Journal, April 19, 1928

“Workmen Find Baby, Believed Abandoned,” Minneapolis Sunday Tribune, May 29, 1921

“Court Bars Northeast Minneapolis Quarry,” Minneapolis Tribune, July 24, 1920

“Judge Upholds Council Authority,” Minneapolis Tribune, June 22, 1922

“Noise Damage Case Before Court Again,” Minneapolis Tribune, Jan. 13, 1921

1501Johnson.com

Left to right: In the 1940s, Johnson Street Commercial Club members Clem Johnson, Loren Peterson, C. C. Wilmot, and Charles Blanchard looked at a map of the proposed Minneapolis athletic field to be built on this site between 16th and 13th avenues Northeast and Fillmore and Johnson streets Northeast. Club President Ralph Sullivan leaned on the sign discouraging dumping at this former quarry, while Maple Hill Booster Club President Donald Dane held up some of the rubbish that was once needed to fill the quarry. Trash dumping made development difficult. (Photo provided by Hennepin County Library) 1938 aerial photo of the vast Johnson Street quarry. 18th Ave. NE is the road along the top, Johnson Street is on the left, Stinson Boulevard on the right, and New Brighton Boulevard is the diagonal street. (Photo provided by Historical Information Gatherers)