Stanley Sentyrz was a big, strapping 16-year-old when he walked through the gates at Ellis Island in 1910. A farm boy, he’d left his native Poland, like so many others, for a better opportunity in America. At Ellis Island he met a family who had friends in Chicago. He also fell madly in love with a girl his age.

Her name was Anna Kowalczyk, and she was not impressed with the young man, who soon found a job at the Hormel killing yards in Chicago. Stanley tried desperately to gain her favor, but Anna wanted nothing to do with him. She moved to Minneapolis. Undeterred, he quit his meatpacking job after just six months and followed her. He persisted in his courtship, eventually winning her hand. They settled down in Northeast Minneapolis and by 1915 were the parents of a boy named Joseph. Another boy, Walter, followed in 1916.

The Minneapolis City Directory for that year shows Stanley working as a fireman at General Electric at 2953 California St. The 1920 directory lists his occupation as “helper.” He must have been looking for something more challenging, because three years later he went into business for himself.

In 1920 the Volstead Act was made law, and Prohibition was soon in full swing. “People couldn’t drink or didn’t have the money to drink,” said Stanley’s grandson, Walt Jr. “He quickly realized that they had to eat. He had a friend, John Pletscher, who he bought the grocery store from in 1923.” (Pletscher, a Swiss immigrant, went on to establish Pletscher’s Greenhouse in New Brighton.)

The store at 1612 2nd St. NE, like many corner grocery stores, carried the basics that everyone needed – flour, sugar, coffee, produce and some meat. In 1933, Prohibition was repealed, and Minneapolis began issuing liquor licenses once again. Stanley Sentyrz got in line.

“We have one of the first five licenses granted by the City of Minneapolis in 1933,” said Walt. “At that time, the city decided that the only establishments that could sell liquor would be pharmacies. Pharmacies already dealt in controlled substances, and they thought they would be ideal to control liquor. My grandfather, with a third-grade education, had by that time learned English, and he petitioned the city fathers. He told them he was a naturalized citizen who ran a grocery store. His argument was, ‘If you give it to them, you have to give it to me.’ And lo and behold, they did!” Today, Sentyrz is the only grocery store in Minneapolis that has a liquor license. Walt said it’s probably the oldest license in the city.

The store supported Stanley, Anna and their five children and earned the good will of folks in the neighborhood. The family was known for their cheerful service and willingness to get customers the products they wanted. According to a 2001 Northeaster article, in the days before refrigerators were a common household appliance, they would open the store on Sunday nights so women could buy lunchmeat for their husbands’ lunches the following day.

When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, their son Walter enlisted in the Army Air Corps the next day. (His draft notice caught up with him two years later.) He spent the war flying transport planes in the African and Indian theaters. In a 1944 Minneapolis Morning Tribune article, he discussed some of his missions, including one in which he was flying between Algiers and Tunis. “As his unarmed transport was winging its way, a Nazi, flying an HE-1-10 that fairly bristled with guns, came on for the kill. It looked like sure death for the transport, until two P-40s – also appearing out of space – did a bit of gunning for the gunner.” The article quoted Walter, “I didn’t wait around to see the end of the show.”

One person he did wait for was Falyce Sadowski. During his training in Detroit, he was invited to a party put on by a doctor who was entertaining people of Polish descent. The doctor’s youngest daughter caught Walter’s eye. But history has a way of repeating itself: Falyce wanted nothing to do with him. The Sentyrz charm won out, however, and they were married in 1945.

“My grandfather became ill in 1950-52,” said Walt Jr. “My dad was still in the service. He was an executive officer for the 934th Air Wing at Ft. Snelling. Dad realized [his dad] couldn’t continue his service and run the grocery store. That’s when he and my uncle Frank took over the business.”

The brothers were close and got on famously, but their wives didn’t. Eventually, Walter bought Frank out and became sole owner of the store, which had been expanded in 1954. Walter quadrupled the size of the store in 1963, tearing down the original corner store and increasing the footprint to 15,000 sq. ft. “At that time, for an independent grocer, it was a huge store,” said Walt Jr. “Today, it’s more like a convenience store.”

Outlasting the competition

About the time Walter Sr. enlarged his store, a well-dressed man showed up early one morning before the store opened, Walt Jr. recalled. “He asked for my dad, and said, ‘Mr. Sentyrz, I have something you need.’ Dad said, ‘Really? What do you have?’ The man said, ‘I have Gold Bond stamps.’ Dad said, ‘I don’t need your stamps, and I don’t need you. You can leave the store.’ With that, Curt Carlson walked out.”

The Sentyrz family encountered Carlson – who had made a fortune with his stamp redemption program and gone on to found the Radisson Hotel chain, again – when a couple of city-owned properties – grocery stores – came up for sale. One was on 18th and University, the other on West Broadway in North Minneapolis. Both had belonged to Carlson. Walt Jr., now the owner of the business, considered buying the University store, but the city wanted a package deal. He walked away, and the Fleming Company leased the store to Rainbow Foods.

For a brief time, Walt Jr. ran two stores, the original on 2nd Street and a Town & County Supermarket in the St. Anthony Village shopping center. “The year after I bought and remodeled that store, Cub built a brand-new store in Apache and Rainbow Foods built a brand-new one at the Quarry. The handwriting was on the wall. I couldn’t compete with those larger stores.”

In 1997, he closed the St. Anthony store and contemplated buying the Rainbow store on 18th and University from Fleming. “Theoretically, I should be able to double my business,” he told the Northeaster. Fleming, however, wanted him to not only buy wholesale groceries and the store fixtures from them, but pay a percentage of his sales to them as well. That was a deal breaker. He told the Northeaster, “I wish them luck and we’ll see what happens in two years.”

In 2002, he decided to expand his store again. There was one problem: In order to get enough parking space to accommodate the expected increase in customers, the duplex adjacent to the store had to go. Built by Stanley Sentyrz, it had maple floors and beautiful woodwork, but it was in tough shape after 25 years as a rental property. Walt decided to give it to anyone who would haul it away. He advertised it on twincitiesfreemarket.org. Three interested parties looked at the property and each put down a $500 security deposit, but none found a way to move the house. Sentyrz eventually had it torn down.

He credits part of his store’s longevity to being “in a food desert,” he said. “I don’t have any competition close by.” Convenience is another factor. As Sentyrz points out, “Anybody can sell you a can of beans.” But having meat butchered at the store (they’re famous for their homemade sausage), fresh produce and alcohol all under one roof makes the store an easy stop for a working family. And groceries are bagged for you, a service that’s gone by the wayside at larger grocery stores.

Sentyrz has kept up with the times, installing rain gardens in his parking lot and solar panels on his roof. “When Dad and I discussed people using credit cards to pay for groceries, we never dreamed of iPhones and Venmo,” he said. He noted the recent trend toward more frequent trips to the grocery store. “People used to shop once for the whole week. Now it’s coming full circle, with people making multiple visits.” Just like they did 100 years ago.

Sentyrz is in his seventies, but he has no thoughts of retiring. “I hate the hours, but I love the work and the people,” he said. His two daughters have no interest in taking over for him, should he decide to take it easy.

A few years ago, his wife, Shirley, asked, “What’s going to happen, Walt, when you die? Who’s going to run the store?”

A great joker, he had a ready answer: “Honey, you don’t have to worry. I told Tommy Glodek I’d buy the biggest casket he’s got, because when I go, I’m taking it all with me.”

Sources

Interview with Walter Sentyrz Jr., June 1, 2023

Minneapolis City Directory, 1916, 1920

“For Crash Landing, City Flyer Likes Jungle,” Minneapolis Morning Tribune, Feb. 23, 1944

“City might challenge commercial corners,” Northeaster, Aug. 26, 1996

“Sentyrz’s grocery move to former Rainbow on University not likely,” Northeaster, Oct. 20, 1997

“Well known NE store owner Walt Sentyrz Sr., dies at age 84,” Northeaster, Aug. 7, 2001

“4 bedrooms, 2 baths, and it’s free,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, Oct. 14, 2002

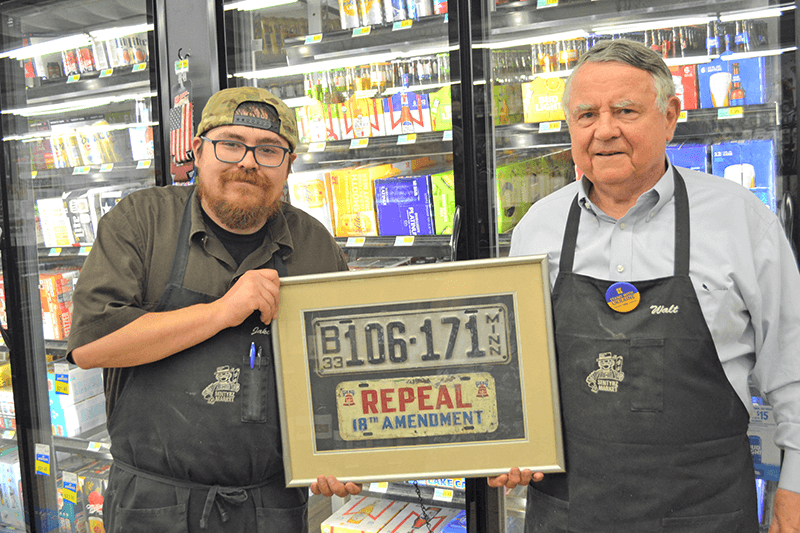

Walt Sentyrz with a photo of John Pletscher’s store, which his grandfather Stanley bought in June 1923. Liquor buyer John Ballad (left) and Walt Sentyrz hold up a piece of antiquity from Prohibition days. (Photo by Cynthia Sowden)