It’s June in 1960s Northeast Minneapolis. The sun is warm and the air is slightly humid. Hundreds, perhaps thousands, of people line St. Anthony Parkway from Fillmore to Johnson, pressed up against snow fences erected along the street, hoping to get a better view. Cletus McGovern, the advertising director for the Minneapolis Argus, is there with his dancing/marching band from St. Lawrence Catholic Church. Men take off their hats and women put their hands over their hearts as the band plays “The Star-Spangled Banner.” The excitement builds as kids line up their home-built race cars along Fillmore. It’s time for the Minneapolis Soap Box Derby.

The Soap Box Derby began in Ohio during the Great Depression and quickly spread throughout the country. Although it continues in many cities today, its heyday in Minneapolis was roughly from the late 1940s to the mid-‘60s.

Although the derby was held in various parts of the city, “Norwegian Hill” from Fillmore to Johnson was a favorite venue. The angle of the hill was sharper then. When you came over the crest in the family car, you took a little plunge that gave you the momentary weightless feeling of a carnival ride. That small degree of difference made downhill racing all the more exciting.

Building the cars

When newspaper photographer Myron Scott came across some Dayton, Ohio, boys racing downhill in wooden orange crates and soap boxes affixed to baby-buggy wheels in 1933, the seed for the Soap Box Derby was planted. Since then, the non-motorized vehicles have always been made from scratch, although they are much sleeker-looking today.

Jerry Houk, a South Minneapolis boy who was the 1959 Minneapolis derby champion and went on to compete at the national race in Akron, Ohio, described the building process for Hennepin History magazine. Although he received advice, Derby rules state that the racer must make the car him/herself. After securing a sponsor (a local grocer and meat market), he went to Harold Chevrolet in downtown Minneapolis to pick up a set of official wheels and axles. (Chevrolet sponsored the nationwide competition.)

“I took my time going through a couple of sets of wheels, spinning each one by hand, to make sure I had four wheels that would run true,” he wrote. “Next I made a trip to the lumberyard for a piece of lumber—2 x 12 x 96 inches—to make the floorboard.”

He installed the brake pedal and the steering mechanism, then built the frame and covered it with sheet metal. Like many racers, he put in thousands of hours to build his car. He named it “Tinker Toy.”

(Today’s would-be Kyle Busches can build a car in a few hours from kits available from the Soap Box Derby store. Kits run from $505 to $830.)

The races

Before World War II, Minneapolis derby races were held on St. Anthony Parkway. In 1958, they shifted to Franklin Avenue, which had a curve in it that favored cars in the left lane. The race moved back to Norwegian Hill in 1959, where there was no lane advantage.

Judges usually included local dignitaries or celebrities. Judges for the 1948 race were Minneapolis Mayor Hubert H. Humphrey, Lee Potter, Jr., and Hennepin County Sheriff Ed Ryan.

There were class divisions: Boys 13-15 raced in Class A; Class B was for boys 11 and 12 years old. Drivers competed against each other in heats. The winner of each heat would race against other winners, gradually eliminating their competition during successive heats. Eventually, one came out a winner. Heat winners received trophies. The champion received a plaque at a dinner at the Leamington Hotel downtown and an all-expenses-paid trip to Akron to compete in the national event.

Houk recalled his 1959 ride down the hill: “My first heat in the race was actually my first time down the hill. At the sound of the starter’s gun, I got a cramp in my leg and thought I would never make it past the first heat of the day. If I sat up or swerved, it would be all over. But I managed to stay in position, with my chest against my legs. It took just under a minute to cross the finish line. I won that first heat with five more heats to go. There was one dead heat out of the six I needed to win, and it was too close for comfort. But I led again, and at the end I received the checkered flag. My dream had come true!”

Houk went to Akron, but finished last in the fifth heat. He later donated Tinker Toy to the Hennepin History Museum.

Girls were allowed to enter the competition in 1971.

Scandal hit the Soap Box Derby two years later in 1973, when 14-year-old Jimmy Gronen of Colorado put an electromagnet in the front of his car. When the metal starting gate fell, the car jerked into motion and put Gronen way out in front of the other cars. In successive heats, the battery wore down, the car became slower and slower and Jimmy was found out.

The Derby was tainted; interest in the race waned. Chevrolet pulled its national sponsorship.

A revival with an artistic spin

Artist Kyle Fokken grew up in western Minnesota, where the terrain is flat. “I think I saw one Soap Box Derby as a kid,” he said.

In 1997, his studio was in the Soap Factory building, 514 2nd Street SE. He thought it might be fun to generate some publicity for the artists in the building by holding a soap box derby with cars designed or decorated by artists. He wrote and won a $1,000 grant and got to work organizing the race.

The first Great Soap Box Derby was held on a downhill run on a cobblestone street. The “track” would have crossed Main Street, passed a cliff and ended up near the Xcel Energy plant on the river. The course was shortened for safety reasons. There were no prizes, plaques or award banquets. The emphasis was on creativity and fun.

The cars had to be able to roll, brake and turn, and drivers had to wear helmets. Construction details were left up to the entrants, but Fokken and friends did conduct some basic car-building classes. With artists involved, the paint jobs were spectacular and the creations fantastic.

Fokken’s wife, Heather, and a friend attempted to make a car out of a clawfoot bathtub, with a tiller in back for steering. When Kyle and a friend took the tub for a test drive, the brake cable broke on the way down and the vehicle careened downhill at 20 mph.

In the following five years, after trying out hills near Hwy. 280 and East Hennepin and the East River Road near the U of M hospitals, the event returned to Norwegian Hill. Friendly Chevrolet in Fridley, which had sponsored races in the ‘60s, lent a hand. Shop teachers at Marcy Open School and Northeast Middle School had their students build cars as class assignments. Because artist members were involved, the Northeast Minneapolis Arts Association (NEMAA) paid for the required $1 million insurance binder.

One metal artist created a dragster from welded steel or aluminum that had a fake engine mounted to it and a parachute on back. Fokken enlisted the aid of Minneapolis Park Board Police, who used a radar gun to record speeds. The car hit 33 mph.

One year, Chanhassen Dinner Theater sent a covered wagon – minus its cover – down the hill with a 90-year-old woman wearing a helmet and sitting in a barrel chair at the helm. The cars also appeared in the Central Parade. Race spectators increased to around 300.

During its six-year run, the Great Soap Box Derby remained a one-man production, with Fokken making all the business arrangements. He decided he wanted to spend more time in his studio; the last race was run in 2002. He has no regrets.

“Sometimes,” he said, “the fun of doing it matters most.”

Sources:

Dickson, Paul, “The Soap Box Derby,” Smithsonian Magazine, May 1995

Houk, Jerry, “Tinker Toy, a dream come true,” Hennepin History, Spring 2006

Olson, Gail, “Northeast will host Soap Box Derby June 20,” Northeaster, June 8, 1999

“Boy, 13, Outspeeds Others to Win Soap Box Derby,” Minneapolis Star, July 26, 1948

“From the Collection: Soapbox Derby Car,” Hennepin History Museum

“World’s Most Infamous Soap Box Derby Car,” RoadsideAmerica.com

Editor’s note: The author’s late husband, Ralph Sowden, grew up in the Waite Park neighborhood and raced in the Soap Box Derby from 1964-67. He was a two-heat winner in 1965.

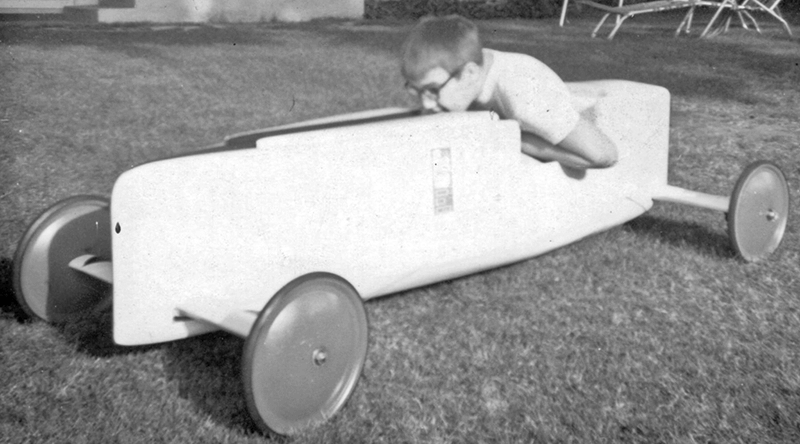

Below: Racers line up before the 1948 race, sponsored by the Minneapolis Star and Minneapolis Chevrolet dealers. Drivers and cars were weighed before the race. The weight limit for the car was 150 lbs.; total weight for car and driver was 250. (Hennepin County Library, Minneapolis Newspaper Photograph Collection) Waite Park driver Ralph Sowden practiced his racing form in the backyard in 1964. Drivers scrunched down behind the wheel to make themselves and their vehicle as aerodynamic as possible. (Provided photo) When artists create race cars, new forms emerge. (Photo provided by Kyle Fokken)