When Bill Volna was in middle school, his science teacher encouraged him and his best friend to attend a Minnesota Astronomical Society lecture at the Minneapolis library. She knew her two students, who liked to perform science experiments in their basements, would be keenly interested.

That evening turned out to be more hands-on than lecture. The group wound up at someone’s home to do some Saturn gazing, and they took the boys along. The kids climbed the ladder to view the skies through a large telescope and asked plenty of questions about the telescope the host was building in his garage, Volna said. “Our lives changed right there. That was a turning point for the two geeks from the seventh grade,” he said. By September of the next year, Volna’s father took the boys and the telescopes they had built to that host’s house for “a little show-and-tell,” Volna said.

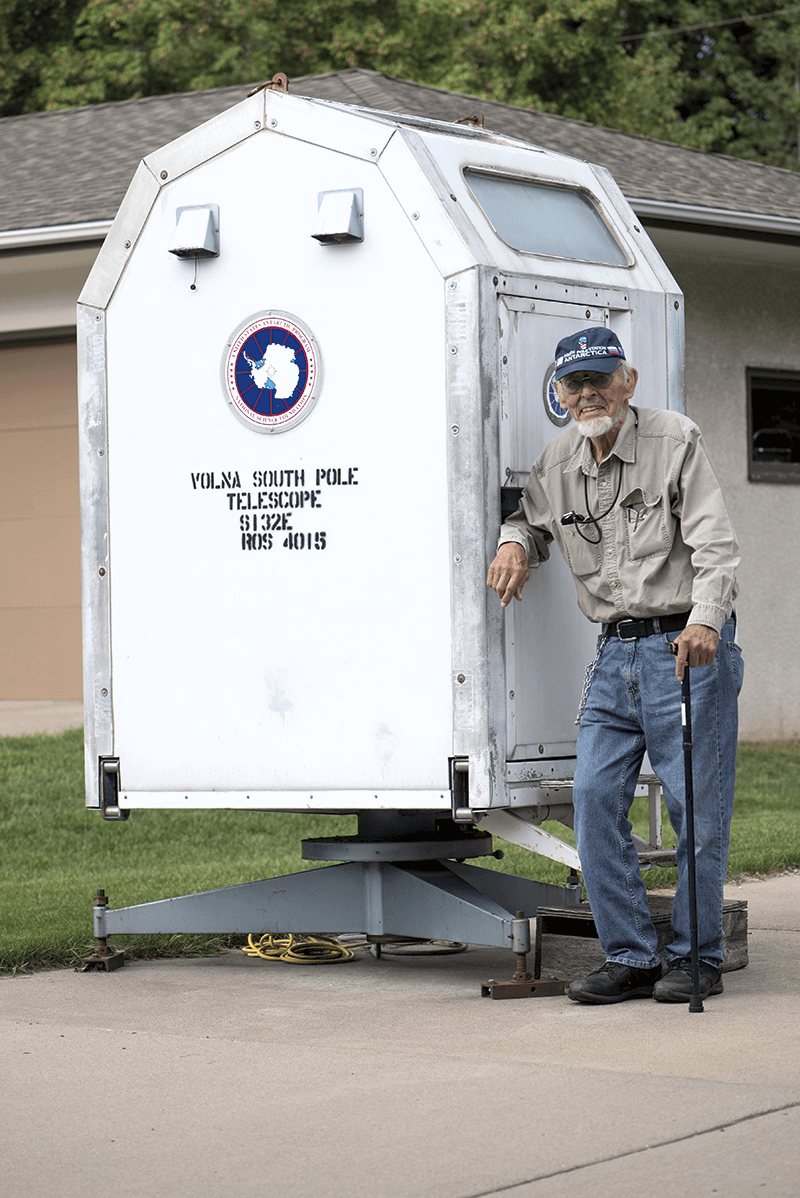

Now 91 years old, Volna reflected on the experiences that led to an engineering career with Honeywell and his years as a consultant out of “The Sandbox,” a concrete block building he and his father built on Quincy Street Northeast. He talked about the inventions he tooled in his machine shop, including a portable observatory that was used in Antarctica and now sits in Volna’s St. Anthony Village driveway.

The Honeywell career started soon after Volna’s 1949 graduation from Edison High School. He was working at the National Tea Company grocery store on the 2800 block of Johnson Street (where Hazel’s is now), when a man dressed in a flight suit, complete with goggles, came into the store.

Curious, Volna engaged him in conversation and learned he had just flown from an air base in California and was a Honeywell engineer. The customer came into the store every week, and Volna would carry his groceries to his home near the Hollywood Theater. “We became really tight buddies every Saturday,” Volna said.

That bond led to an invitation to show his telescopes (with lenses he had ground himself), and other devices he had built to a group of Honeywell engineers. Volna was a first-year mechanical engineering student at the University of Minnesota, and a Honeywell vice president who came down to inspect his work offered him a job.

At Honeywell’s Aerospace Division, he contributed to the development of various navigation and positioning devices while finishing his 5-year degree. He was there 19 years, and toward the end of his stint he laid the foundation – figuratively and literally – for his own engineering business.

He purchased a lot at 1808 Quincy Street NE, got his hands on plans from a telephone company building going up in Columbia Heights (“so that I could look at the way architects make drawings, which is not the same as a mechanical engineer,” he said), then drew up plans of his own.

After work, during evenings and on weekends, he and his father poured footings and laid more than 4,000 concrete blocks, Volna said. Using the paid-for building as collateral, he took out a loan to get his business off the ground, populating the building with worn out machine shop equipment, which he repaired.

When Volna arrived at Honeywell as a 19-year-old, he already had a lot of experience in making things. He had a lathe in his basement, materials for glassblowing and grinding lenses. He said he was known at Honeywell as a “dirty-fingered doer,” someone who not only could conceive of designs but build them as well. Honeywell engineers turned to him as an independent contractor to help design and build devices for them, such as high-precision testing tables, accurate to one arcsecond – 1/3600 of an angular degree.

Gil Mros was an electrical engineer at Honeywell, working on the electrical components of a tester for an infrared detector array used on a military project. Mros said he was struggling with the mechanical aspects of the design and a friend suggested he call Volna, who then designed and built a unit that met and, in some respects, exceeded the requirements. “I guess you could say Bill bailed me out,” Mros shared in an email. “Over the years I found that Bill’s dependability, attention to detail, and drive toward perfection extended to his other projects as well as mine.”

Volna wound up on the Honeywell payroll again in the early 1990s, at the Aerospace Division’s Systems and Research Center, after having done a lot of consulting work for the center. Fred Faxvog, an engineer there at the time, said Volna would always bring problems back to fundamental principles of physics, the basics of mechanical engineering. And he wouldn’t just go off and solve the problem himself: He’d show his colleagues, some of them decades younger than him, how to solve it. “He’s a real teacher of the craft. He wanted to teach the younger guys how to go about it,” said Faxvog.

That included Faxvog’s cousin, an electrical engineer who decided to convert his gas-powered car into an electric one. After removing the engine, he couldn’t figure out how to best mount the electric motor. “Oh, call Bill,” Faxvog said he told him. Volna coached Faxvog’s cousin in determining the motor’s center of gravity and using that in deciding how to mount it.

Working as an independent contractor allowed Volna to pursue his own projects, including a solar tracker that could orient solar arrays in optimal positions over the course of a day, and a solar-powered desalination unit.

One of Volna’s inventions – and Volna – wound up in Antarctica. He had been invited to an astronomers’ sky viewing party one March and became thoroughly chilled. “I said, ‘If I ever come back to this hobby, I’m going to do something about the problem of mosquitoes and being cold.’”

His solution was an enclosed, portable observatory that took him nine years to build. He took it on a trailer to astronomy groups all over the country and wrote about it for the magazine Sky and Telescope. Astronomers nicknamed it “Tardis” after the time machine in the TV series Dr. Who. At a viewing event south of Chicago, a scientist approached him about making one to use for an NSF-funded project at the South Pole, for atmospheric studies. Volna told him that he could take the existing one, on one condition – that he be allowed to go with it. After testing in Minnesota in a controlled environment of 100 degrees below zero, the Tardis spent a year in Antarctica, and Volna, one month, during the South Pole summer.

As Volna recounts the details of his engineering accomplishments and the stories behind his inventions, he frequently checks for his listener’s understanding. He is enthusiastic and engaging. His frequent reminders such as, “Now, I don’t want this coming across like I was the only one who did this – it was a team,” give a glimpse into what he might have been like as a colleague.

Volna and his engineering friends, including Mros, still meet on Mondays for lunch at the Great Moon Buffet in Columbia Heights. Sometimes, Mros said, they bring “show and tell” items to “liven up the conversation.” “Bill is unique because he always carries a jackknife, screwdriver, flashlight, vice-grip pliers and who knows what all else in his pockets to make sure that whatever object or artifact gets a thorough examination,” Mros explained.

“The subjects we discuss vary all over the map, but one of the things I enjoy most is Bill’s ability to express his ideas not only with words, but with the sketches that he makes on napkins with his fine point Sharpie marker. Sometimes I feel I should keep them in a scrapbook instead of leaving them in the restaurant,” Mros shared, adding, “My initial business relationship with Bill turned out to be the beginning of a lifelong friendship.”

Faxvog said Volna has a gift for connecting with people, and loves to plan social events, such as their yearly picnic. “It’s all about relationships,” Faxvog said about their conversations and get-togethers. “Not an introvert by any means. He’s just a well-rounded mechanical engineer.”

Below: Bill Volna with his solar tracker, one of his many inventions. The portable observatory he designed and took to Antarctica to study the stars. (Photos by Karen Kraco)

![]()