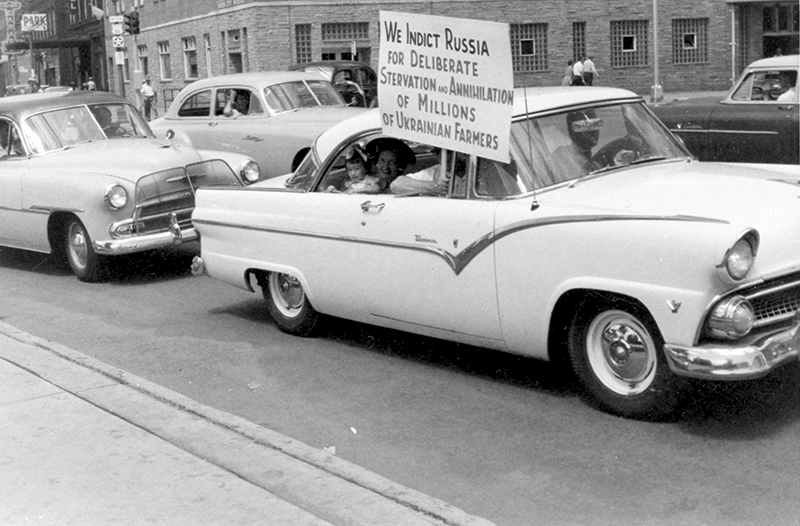

Minneapolis Ukrainians protested the Holodomor in 1932. (Semeniuk Family)

Zina Gutmanis grew up in Northeast’s Ukrainian community. Although she sometimes heard references to “Holodomor,” she didn’t really understand it. “I didn’t think it had anything to do with me,” she said in a recent interview.

Until 2015, when she was invited to join a committee on the Ukrainian Holodomor Genocide Awareness Board.

The committee was charged with putting a monument on federal land to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the Holodomor, an artificial famine imposed on Ukrainians by Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin in 1932-33.

Ukraine has long been the “breadbasket” of Europe, and its farmers fiercely independent. Most of them were small landowners, and they resisted the collectivization of farms. Those who resisted most vociferously were termed “kulaks (fists)” by the Soviets. They were rounded up, their lands and household goods confiscated and were sent to penal colonies or executed.

In 1932-33, Stalin decided to crack down further. He implemented a “Five Stalks of Grain” policy: Anyone, children included, caught taking produce from a collective field, could be shot or imprisoned for stealing “socialist property.” At the beginning of 1933, about 54,645 people were tried and sentenced; of those, 2,000 were executed.

Systematic starvation of farming communities included sealing Ukraine’s borders so farmers couldn’t go elsewhere to work; collective farms that didn’t meet production quotas were blacklisted and surrounded by troops so that people could not get out to get supplies. Desperate Ukrainians subsisted on grass, acorns, pets, while the Soviet government took more than 4 million tons of grain — enough to feed 12 million people for a year — out of Ukraine.

The University of Minnesota Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies (CHGS) has documented the Holodomor through oral histories and photographs. According to CHGS, it’s “impossible to determine the precise number of victims of the Ukrainian genocide, most estimates by scholars range from roughly 3.5 million to 7 million (with some estimates going higher). The most detailed demographic studies estimate the death toll at 3.9 million.”

It was while doing committee work that Gutmanis realized that she had known and gone to church with Holodomor survivors all her life, and that they were becoming fewer in numbers with the passing years. She applied for a grant from the Minnesota Historical Society to collect oral histories; her grant manager encouraged her when she floated the idea of making a film.

She interviewed 13 people in all, including not only Holodomor survivors but Ukrainian soldiers who came the U.S. to receive prosthetics for injuries they incurred during the current war. Her father, Alexander Poletz, who lives in St. Anthony, served as interpreter.

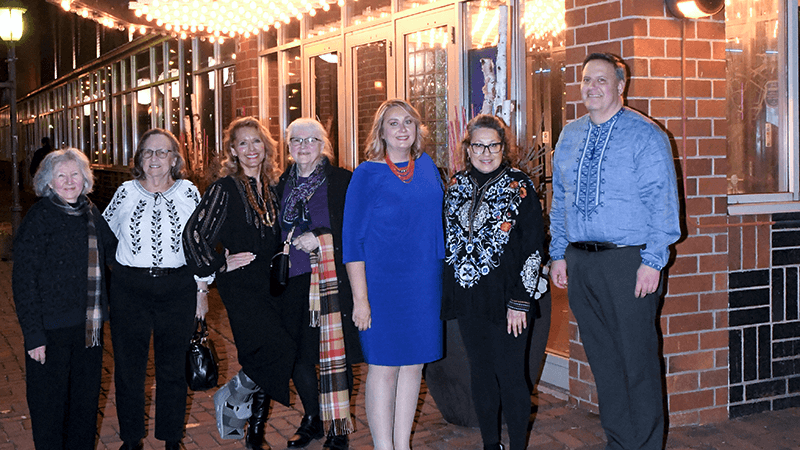

“Holodomor” filmmakers at the Main Cinema for its premier in November 2023. Left to right, Tamara Niepritzky, project treasurer; Wanda Bahmet, project advisor; Helen Chorolec, film interviewee; Halyna Myroniuk, retired U of M librarian and film research consultant; Zina Poletz Gutmanis, film writer/director; Orysia Bobcek (lives in Northeast), St. Michael’s and St. George’s Ukrainiain Orthodox Church board president at the time and film advisor; Taras Pidhayny (lives in St. Anthony), St. Constantine Ukrainian Catholic Church board and film advisor. (Provided)

The interviews were buttressed with research at the U of M, Holodomor Research & Education Consortium at University of Alberta, Canada, and Holodomor Museum in Kyiv.

Poletz was born in 1935, after the Holodomor. His father was an engineer on a railroad for a railway the Communists deemed important, so the workers were given a food stipend. Poletz said his father was hounded continually about joining the communist party. “He realized that he could not be with them morally and ended up taking a lesser position, a chain man on a survey crew.” The family moved four times before coming to America.

One of the people Gutmanis interviewed was Olga Chorolec of Columbia Heights, who passed away in 2019 at the age of 90. Her daughter Helen said Olga was a girl of 10 or 12 when the Holodomor occurred. “My grandparents always talked about it when they got together with people,” Helen Chorolec said, “and I learned about it in Ukrainian school.

“It really affected my parents and grandparents. They had to save food — heaven forbid if you threw anything out. If it was moldy, you put it outside for the animals. Food was love. When I went to college, my grandmother would load me up with food. That was caring. When we visited relatives, it was like Thanksgiving dinner; my mother said it was how they showed their love.”

Chorolec said they didn’t trust banks, because the state was behind them. They always carried cash. And “you kept your head down, didn’t call attention to yourself.”

She said Olga’s last words were, “We have enough food to eat and drink, but we don’t have life.”

Another participant in the filming was Rev. Myron Korostil of St. Michael’s and St. George’s Ukrainian Orthodox Church, 505 4th St. NE.

“Holodomor: Minnesota Memories of Genocide in Ukraine” had a private premiere in November 2023 at the Main Cinema. It made its television debut on Jan. 5 on TPT’s Minnesota channel and was rebroadcast several times on Jan. 13. It will be shown once more at 9 p.m. on Jan. 31 on TPT-LIFE.