There are 50,000 square miles of turf grass in the United States. Chances are, some is in your own front yard. While some enjoy fertilizing, watering and mowing the lawn on a weekly basis, others would just as soon not mow at all, earning the frowns of their next-door neighbors.

There’s an alternative to these two extremes that’s earth-friendly, low maintenance and looks good. It’s called a “bee lawn,” and if weather conditions are right, you could easily reduce your mowing schedule to once a month.

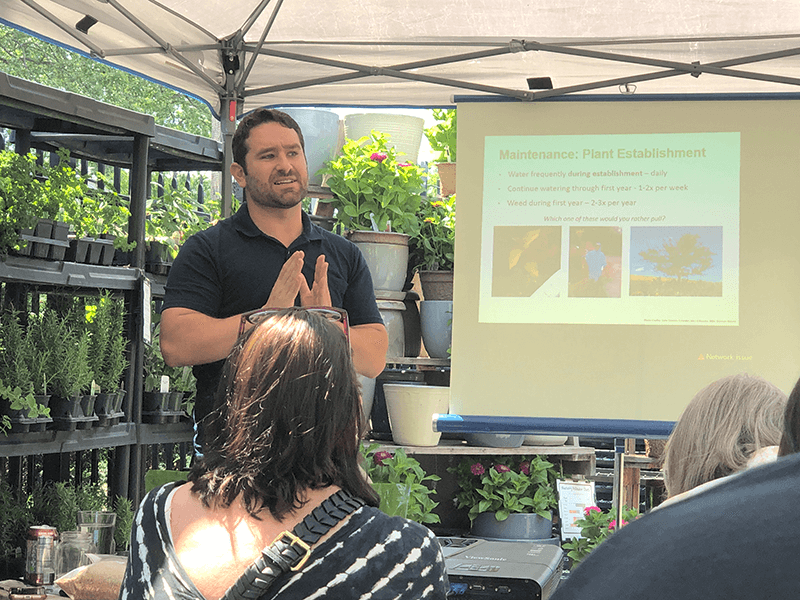

James Wolfin is a conservation specialist with Edina-based Twin City Seed Company. (He’s also the company president.) He gave a talk about bee lawns at Mother Earth Gardens, 2318 Lowry Ave. NE, on July 28.

“There’s three times more acreage in turf grass than there is in corn,” he said, “ and most of it is in the cities and the suburbs.”

Keeping those acres of Kentucky bluegrass healthy is expensive, too. A turf lawn requires 3 lbs. of nitrogen annually to maintain its good looks. Unfortunately, a lot of that nitrogen washes off during a rainstorm and gets flushed down city sewers.

A bee lawn, on the other hand, requires very little fertilizer — maybe a half-pound per growing season. Furthermore, it’s low maintenance and it sends down deeper roots than bluegrass, making it drought tolerant. Those deep roots also allow water to infiltrate the soil instead of washing away. It also has a slow rate of vertical growth: It seldom gets taller than 6 inches and requires less mowing.

Wolfin has worked with the University of Minnesota to come up with a seed mix that produces an environment that’s attractive to pollinators and homeowners both. He spent many days in Minneapolis parks observing pollinators and the flowering plants they were drawn to. Ninety-five percent of the “visitors” he observed were native species.

Pollinators, he said, seek plants that have a “high value.” “They have to provide pollen and nectar equally,” he said. “There’s a high amount of sugar in nectar and high protein in pollen. That’s what bees want in their forage.”

Wolfin identified three plants that have the “right stuff:” Dutch white clover, creeping thyme and self-heal, a purple-flowered plant in the mint family. He noted that clover used to be part of every lawn seed mix, because it fixes nitrogen into the soil. “Then the lawn care companies discovered they could make money selling herbicides to get rid of it and create a totally bluegrass lawn.”

Clover draws all types of bees, although larger bumblebees may have trouble finding enough landing space. Smaller bees, such as sweat bees climb into a flower and gather pollen in the sacs on their legs.

Clover blooms all summer long. Creeping thyme blooms in August and September. Self-heal will flower from June to October. Another flowering plant that’s good for bee lawns is the common purple violet, which blooms in spring, although it’s difficult to gather enough seeds to include it in a mix.

Wolfin also experimented with yaak yarrow and blue-eyed grass. They’re included with some seed mixes, although those two plants are not quite as winter hardy as the others. (Dandelions, coincidentally, are not a “super food” for pollinators.)

A good bee lawn mix also includes grass. Fine fescues are grasses that will grow in sun or shade and are winter hardy. They also germinate quickly and are allelopathic — they can inhibit the growth of weeds. And they don’t require a lot of mowing.

Now is the best time of year to seed a bee lawn, up until Sept. 15 or a little later. (Spring is another optimal time.) You can overseed your existing lawn or dig it up and replace it entirely. Dormant seeding — spreading seeds just after the first frost — is another way to start a bee lawn; the seeds will sprout next spring. You can also use it as a patch for bare spots. Mother Earth Gardens has seed mixes and starter plants, as well as planting instructions.

With a little work now, you can have a “slow-mow summer” next year.

James Wolfin, Twin City Seed Company, explained how to establish a bee lawn during a presentation at Mother Earth Gardens last month. (Cynthia Sowden)